Key words: Africa, diaspora, knowledge democracy, brain gain, collaboration+

INTRODUCTION

The African diaspora, comprising over 50 million individuals globally, represents a vast untapped potential for transformative development across the continent (Edeh, Osidipe, Ehizuelen, & Zhao, 2021). Despite this rich reservoir of skills, knowledge, and resources, effectively harnessing this potential remains challenging due to historical, socio-economic, and governance factors (Chikanda, Crush, & Walton-Roberts, 2016; Edeh, Zhao, Osidipe, & Lou, 2023).

The discourse on African emigration has shifted from a 'brain drain' paradigm to more optimistic notions of 'brain circulation,' recognising positive impacts such as remittances, skill repatriation, and knowledge exchange. While some African countries have enacted diaspora-focused policies, implementation issues persist, often side-lining broader knowledge exchange opportunities.

Current diaspora engagement initiatives, including grassroots associations, capacity-building programs, and philanthropic endeavours, demonstrate potential but face challenges in sustainability and alignment with local needs. This paper identifies a significant gap in the literature: the lack of a unifying framework that consolidates individual efforts into a cohesive impact strategy and provides mechanisms for sustaining long-term engagement.

By applying the coloniality theory, this study aims to uncover hidden power dynamics and knowledge hierarchies that hinder full diaspora participation in African development. This paper explores the lived experiences of diaspora professionals and African stakeholders to develop a framework for equitable and inclusive diaspora knowledge democracy, using the coloniality lens as a theoretical framework. We define the unit of analysis as the individual and collective experiences and perspectives of these diaspora professionals and institutional stakeholders.

Key findings reveal complex factors driving emigration, challenges in diaspora engagement, and potential solutions for narrowing development gaps. This paper concludes that by reconceptualising diaspora engagement and moving towards strategies emphasising knowledge sharing and active participation, Africa can harness its global human capital to catalyse equitable and sustainable development. The proposed framework offers a pathway to create an environment marked by recognition, respect, and reciprocity, essential for fostering a truly inclusive African knowledge democracy.

LITERATURE REVIEW

The term 'diaspora' itself has evolved, mirroring the complexities of migration (Britannica, 2024; Dufoix, 2011). While historically associated with forced displacement, slavery, civil unrest, and colonialism, it has come to also encompass the modern dynamics of voluntary migration and economic expatriation (Gevorkyan, 2022; Zeleza, 2019; Agunias & Newland, 2012). Despite this expanded definition, existing categorisations, like 'migrant' or 'expatriate,' can impart a transient or privileged status that fails to encompass the diverse contributions of these individuals irrespective of their settlement or socio-economic status (Andresen et al., 2022). Such labels carry political undertones, often marginalising diaspora communities in socio-political discourse by perpetuating otherness (Levitt & Jaworsky, 2007; Brubaker, 2005). It may suggest a sense of otherness or foreignness that can impact how migrants are perceived and treated, potentially leading to stereotypes, discrimination, or exclusion (Castles, de Haas, & Miller, 2013; Anderson, 2019). This paper posits a re-conceptualisation of diaspora engagement, valuing all contributions from mobile and settled persons alike as vital to Africa's development.

Historically, the 'brain drain' paradigm dominated discussions on emigration, highlighting concerns over human capital flight from African nations (Docquier & Rapoport, 2012; Martin & Papademetriou, 1991). This narrative has since transitioned towards optimistic notions of 'brain circulation,' lauding the positive impacts of remittances, skill repatriation, philanthropy, and knowledge exchange (Alem, 2016; Gnimassoun & Anyanwu, 2019). Such a shift has spurred countries like Ghana, Nigeria, Kenya, and Rwanda to enact diaspora-focused policies, endeavouring to capture the beneficial impacts (Gamlen, 2006; Rustomjee, 2018). These policy frameworks, while proactive, often grapple with implementation issues, including bureaucratic rigidity and a predisposition toward economic incentives and high-profile diaspora, consequently side-lining the broader spectrum of knowledge exchange.

Grassroots diaspora associations and networks, such as the African Academy of Sciences (AAS) and the Network of Diasporic African Scholars (NDAS), have emerged as pivotal in supporting continental collaboration amongst African scholars in the diaspora (Langa, 2018). Their role in facilitating intellectual discourse is undeniable, yet they are frequently beleaguered by funding inconsistencies and difficulties in achieving widespread engagement, which undermines their sustainability (Kuznetsov, 2006). Likewise, capacity-building initiatives such as the Council for the Development of Social Science Research in Africa (CODESRIA) and the Carnegie African Diaspora Fellowship Program (CADFP) have made inroads in fostering scholarly communities, but strategic planning and sustainable funding are requisites for ensuring that such impacts endure (Zeleza, 2013).

In the academic arena, initiatives spearheaded by higher education institutions, including the Diaspora Engage program by the University of Ghana and the Diaspora Advisory Board at the University of Cape Town, underscore the potential for universities to nurture diaspora relations. These programs, however, are not immune to challenges, such as faculty and institutional stability, which can disrupt long-term diaspora engagement, highlighting the necessity for institutional commitment and continuity (Pratt & de Vries, 2023).

Philanthropic endeavours also play a noteworthy role in creating educational and scholarly opportunities, for example, the Next Einstein Initiative and Rhodes Scholarships. Despite their contributions, these programs are often limited by their alignment with donor interests, which do not always resonate with local needs, and by the perennial challenge of securing sustainable funding (Knittel et al., 2023).

Through this examination of existing diaspora engagement initiatives, it becomes clear there exists a significant gap within the literature—a deficiency in a unifying framework that consolidates individual efforts into a cohesive impact strategy. Also, it does not provide sufficient analysis of the mechanisms necessary for sustaining long-term engagement through systematic support and collaboration. This gap emphasises the need for a comprehensive approach that assembles the fragmented landscape of diaspora contributions.

This integrative approach predicates the need for a framework cognisant of the enduring legacies of colonial history on diaspora interactions. The diaspora's relationship to their homelands is often framed within contexts established during colonial rule, with remnants influencing both policy and perception, limiting potential contributions across borders (Ndlovu-Gatsheni, 2015). It is evident that an examination and deconstruction of colonial legacies embedded within current diaspora engagement strategies are required to foster a more equitable and effective model of collaboration.

THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

The theoretical framework of coloniality provides a critical lens for understanding the persistent power structures and knowledge hierarchies that continue to shape global interactions in the postcolonial era, despite the formal end of colonial rule. Originating in the Latin American decolonial movement, coloniality theory dissects the enduring power structures and knowledge hierarchies that persist despite the formal end of colonial rule influencing culture, labour, intersubjective relations, and knowledge production, even after the dismantling of colonial administrations. (Mignolo, 2011; Quijano, 2007; Maldonado-Torres, 2007; Dussel, 1995).

The coloniality theory has evolved to encompass a global perspective, recognising its impact not only on former colonies but also on the colonising powers. Scholars have examined its economic dimensions, highlighting unequal economic relations between the Global North and South (Grosfoguel, 2011), as well as its cultural aspects, exploring how colonial ideologies continue to shape identities and social practices (Maldonado-Torres, 2007).

In this paper, we found the coloniality theory particularly relevant for analysing the complex relationship between the African diaspora and their homelands. Specifically, the focus was on how the legacies of colonialism continue to influence engagement policies and practices, shaping how knowledge is produced, shared, and valued. It reveals how Western-centric narratives have historically marginalised African epistemologies, culture and innovations, creating a hierarchy that privileges certain forms of knowledge over others (Elabor-Idemudia, 2021; Kessi et al., 2020; Ndlovu-Gatsheni, 2015; Quijano, 2007; Grosfoguel, 2007). Additionally, the coloniality of migration (Grosfoguel, 2013) demonstrates how contemporary policies often mirror colonial-era restrictions, hindering diaspora engagement (Mbembe, 2017).

Recent scholarship has expanded on the concept of coloniality, exploring its intersections with race, gender, and class (Ndlovu-Gatsheni, 2018). This nuanced understanding allows for a more comprehensive analysis of the challenges and opportunities in diaspora engagement. By deconstructing these power dynamics, we can work towards a more equitable and inclusive model of knowledge democracy that values diverse perspectives and dismantles structural barriers to participation.

Within the broader field of postcolonial studies, coloniality theory intersects with other critical frameworks such as decoloniality and postcolonial feminism. Decoloniality, as articulated by scholars like Mignolo (2011) and Walsh (2013), emphasises the need to delink from Western-centric epistemologies and ontologies, advocating for the recognition and revitalisation of indigenous knowledge systems. Postcolonial feminism, represented by the works of Spivak (1988) and Mohanty (1984), critiques the gendered dimensions of colonialism and neocolonialism, highlighting the unique experiences and perspectives of women in the postcolonial world.

While a valuable tool, coloniality theory has limitations. Some critics argue that it can be overly deterministic, neglecting agency and resistance (Prakash, 1995) and that it can essentialise experiences of colonialism (Cooper, 2005). Additionally, it has been criticised for its potential Eurocentrism and for oversimplifying complex realities. The theory may also underemphasise agency and overlook the diversity of experiences across the African continent.

Despite these limitations, coloniality theory remains a powerful framework for understanding the complexities of diaspora engagement in Africa. This theoretical framework informs our study design, data collection, and analysis techniques. By interrogating current diaspora engagement approaches and conceptualisations of the diaspora itself using the coloniality theory, this paper underscores the urgency of moving toward strategies that emphasise knowledge sharing and active participation. The resulting framework advocates for a dismantling of the divides that have long segmented talent across the African diaspora while fostering strengthened relationships that capitalise on the synergistic possibilities found across diverse diaspora backgrounds. It is only through such inclusive, forward-looking approaches that the continent can harness the full spectrum of its global human capital and catalyse a development trajectory that is not only sustainable but also equitable and reflective of its rich diversity.

In delineating this comprehensive framework for diaspora engagement, empirical evidence such as the proactive initiatives undertaken by transnational African science communities during the COVID-19 pandemic (Shaw, 2021) and successful partnerships between diaspora networks, local communities, and governments will be instrumental. These instances provide invaluable insights into creating responsive and sustainable engagement strategies that reflect the complex realities of the African diaspora.

RESEARCH QUESTIONS

The study was guided by the following research questions:

- What factors drive the emigration of African diaspora and how do these impact their willingness to contribute to African development?

- What challenges do African institutions face in engaging with and transferring knowledge from the diaspora?

- What are potential solutions for narrowing development gaps and promoting inclusive growth in Africa?

- What framework of diaspora engagement can be derived from these solutions?

METHODOLOGY

This paper was drawn from a qualitative study to obtain an in-depth understanding of diaspora professionals' and African stakeholders' experiences and perspectives. Qualitative methods facilitate the exploration of complex social phenomena through nuanced, contextual insights not easily quantifiable (Creswell & Poth, 2018). Purposive sampling was used to select 25 diaspora professionals and 15 stakeholders from professional networks, organisations, and conferences. Data collection involved semi-structured interviews lasting 40-45 minutes using carefully designed interview guides based on literature and theory.

Interviews were transcribed verbatim, and thematic analysis was employed using NVivo software to identify, analyse, and report themes. The research team iteratively reviewed codes and themes to ensure an accurate representation of the data.

Thematic analysis identified, analysed and reported themes to provide a rich interpretation (Braun & Clarke, 2006). NVivo assisted in organised, efficient coding. Researchers reviewed codes and themes iteratively to accurately represent data.

Trustworthiness was established through various processes. Credibility involved members checking to confirm the accurate interpretation. Thick description enhances transferability for other contexts. An audit trail maintained through documentation ensures dependability. Lastly, reflexive journals and peer debriefing achieved confirmability by mitigating bias.

Given the theoretical lens, reflexivity and positional awareness recognised the researchers’ background could influence interpretation (Haraway, 1988). An ongoing reflexive practice bracketed assumptions for transparency.

We acknowledge the limitations relating to the relatively small sample size may limit the generalisability of findings also considering that the sample may not fully represent the diversity of the African diaspora or the continent's various regions.

Additionally, qualitative analysis inherently involves subjective interpretation, which we have attempted to mitigate through rigorous coding practices and peer review. Lastly, the cross-sectional nature of the study captures perspectives at a single point in time, potentially missing longitudinal trends. Through acknowledging these limitations, we aim to provide a transparent and nuanced analysis, contributing to the ongoing scholarly discourse on diaspora engagement and knowledge democracy in Africa.

FINDINGS

The findings from this study illuminate the intricate dynamics that shape the relationship between the African diaspora and their home continent, revealing both the challenges and opportunities inherent in their engagement. Through the lens of coloniality theory, we uncover how historical power structures and knowledge hierarchies continue to influence contemporary diaspora experiences and aspirations, addressing our research questions on factors driving emigration, challenges in engagement, and potential solutions for inclusive growth.

Factors driving emigration and the consequences

Addressing our first research question, we found that economic disparities, political instability, and the pursuit of better opportunities emerge as key drivers of emigration among African diaspora professionals and innovators. The allure of advanced economies and the promise of professional growth often compel individuals to seek livelihoods abroad. However, their journeys are not without obstacles, reflecting the persistent influence of coloniality in shaping global mobility and opportunity structures.

Many participants encountered systemic barriers in host countries, including the non-recognition of qualifications, cultural adjustment challenges, and discriminatory practices. These experiences underscore the enduring impact of colonial legacies on contemporary migration patterns and integration processes. As one participant noted:

"It was a bit of a rude awakening to discover international experience and qualifications are not always valued as highly as domestic ones, contradicting my initial assumption that my degree would smoothly transfer over. But I have since learned cultural adjustments take time and have continued pursuing opportunities to contribute my skills wherever possible while also considering additional training options that may improve my competitiveness in this market."

This narrative aligns with coloniality theory's emphasis on the persistence of hierarchical knowledge structures that privilege Western credentials over those from the Global South. The experiences of innovators seeking support for their projects further illustrate the challenges stemming from colonial-era governance structures. One green power developer shared:

"I called the President’s Office and I told them about my projects as well as where I was coming from. They asked me to bring a DVD with the videos and a short presentation as well as a letter stating what I wanted from the President. They also suggested that I should leave another DVD at the Ministry of Science and Technology office. I did exactly what I was told to do. I waited for a response but none came."

This account demonstrates how bureaucratic inefficiencies, often rooted in colonial administrative legacies, can impede innovation and contribute to brain drain (e.g. Carbajal and Calvo 2021; Khalid and Urbański 2021; Zanabazar et al. 2021).

Highly skilled migrants, too, narrated tales of economic despair and political volatility back home, which pushed them to seek safety and prosperity abroad. However, the idealised expectations of employment in the host country often collided with the harsh reality of unrecognised qualifications and systemic barriers, as corroborated by the findings of Thondhlana et al. (2016). These individuals encounter a gamut of disabling factors: denied recognition of credentials, inflated tuition fees reserved for foreign students, cultural and language barriers, and discrimination—frequently forcing them into positions that underutilise their skills if they manage to find employment at all.

This complex interplay of factors propelling and discouraging the mobility of diaspora professionals and innovators underscores the persistent influence of coloniality. This is evident in the lack of infrastructural and institutional support for professionals, resulting from historically entrenched disparities. Works such as those by Nkrumah (1965) on neocolonialism and its impact on economic structures, and Mamdani (1996) discussing the lasting effects of colonial governance, provide historical context to the current disparities. Modern studies offer empirical evidence of the direct correlation between these historical disparities and the present-day brain drain phenomenon reinforcing the understanding that the scarcity of support for local talent is rooted deeply in the enduring shadows of colonial history.

Factors determining diaspora professionals’ and innovators’ willingness/decisions to contribute to their home countries

Transitioning to our second research question, we explored the factors determining diaspora professionals' and innovators' willingness to contribute to their home countries. Despite the challenges they face, many diaspora members demonstrate a strong commitment to African development, driven by complex personal and cultural motivations.

Individual factors such as familial responsibility, experiences of marginalisation abroad, national pride, and the aspiration to return home fuel the desire to contribute to homeland development. As one participant expressed:

"When you see what is happening back home, particularly in the health sector, there is a lot of frustration, because you always wonder 'Why can't things not be like the way you see here?' It's not that people are not intelligent, but they don't have the resources, or things have been mismanaged."

This sentiment reflects the tension between the desire to contribute and the recognition of structural challenges, a dynamic that coloniality theory helps explain by highlighting the persistent inequalities in resource distribution and governance.

Cultural expectations and perceived obligations also play a significant role in motivating diaspora engagement. One entrepreneur, inspired by personal experience, initiated a dialysis centre in her home country:

"When you go to dialysis centres at home, you see loads of people who need help. Some cannot afford to pay and they are left to die. So we decided to help by offering dialysis treatment to about ten poor patients per month for free."

This example illustrates how diaspora members leverage their transnational positions to address development gaps, challenging the notion of a simple "brain drain" and showcasing the potential for "brain circulation" as conceptualised in recent diaspora studies.

These personal drivers, which include both emotional ties and strategic decisions, are echoed in research noting the prominence of identity, homeland pride, and developmental aspirations (Kopchick et al 2022; Madziva et al 2021; Thondhlana and Madziva 2018).

The challenges and potential solutions for African institutions to engage the diaspora

Our third research question focused on the challenges African institutions face in engaging with and transferring knowledge from the diaspora. The findings reveal a complex interplay of structural, cultural, and institutional factors that hinder effective collaboration. We combined the challenges with the fourth research question on suggested solutions as these were usually tackled by participants as a unified response.

Analyses from studies such as those carried out by Shin et al. (2022) and Olayiwola et al. (2020) have pointed towards a dichotomy where, on one hand, the African diaspora is seen as a beacon of hope and, on the other, engagement with them is fraught with systematic, policy-induced, and sociocultural hurdles. Insights from scholarly works (Brinkerhoff, 2012) and narratives from participants provided a nuanced understanding of the multifaceted barriers at play including the following challenges and suggested solutions.

Trust and physical presence in business operations

The issue of trust, or rather the lack thereof, in doing business from afar was a major concern as a participant noted:

"You hear stories about not doing business in Africa if you are not physically present. People tell you of how they've been burned, and how you're not there. Oh, they're going to siphon your money. Oh, they won't do the job, they won't do this, and they won't do that."

Echoing a similar challenge, one academic who sought reintegration with a former institution expressed sentiments of being labelled unpatriotic:

"I was told that my former Vice Chancellor would never be accepted back as my former colleagues viewed diaspora academics as traitors who were quick to desert their institutions at the slightest sign of economic problems."

The experience of being labelled as unpatriotic was dismissed by Baser & Swain (2009) who viewed embracing diaspora academics as promoting 'brain circulation' thereby enriching both their host and home countries. However, institutional resistance and stigma often challenge their reintegration, as noted in their research.

Participants suggested that to mitigate this issue, African institutions could develop secure platforms for business transactions that assure both parties. As one noted:

"Possible solutions could include providing legal support for diaspora investors and creating transparent mechanisms for project monitoring. Fostering partnerships with reputable diaspora organisations can also help build credibility."

Additionally, participants also highlighted the need for educational institutions to actively promote programs that facilitate the integration of diaspora members, such as temporary or virtual returns. Promoting success stories of diasporic contributions can change perceptions and highlight the value these academics bring. Utilising technology to create robust and secure platforms for virtual engagement of the diaspora in mentoring, consultancy, and knowledge-sharing can help in overcoming some of the barriers caused by distance. Reinforcing collaborations between diaspora academics and home country institutions through joint research projects and academic exchange programs can help by tapping into cutting-edge research and educational resources.

Corruption and institutional reliability

Corruption emerged as a recurring theme, particularly from the institutional participants as one explicated:

"The problem with Africa is still that of corruption. We sat down with the government officials and tried to convince them to consider diasporans as we would get the cheapest possible price... but they weren't buying into it. We suspect that the officials wanted a bribe."

The account of government officials demanding bribes points to a larger issue that has been well-documented in the literature (Brinkerhoff, 2012). Corruption not only hampers direct investment but also tarnishes the perceived credibility of institutions, which is crucial for the diaspora's involvement.

Participants considered policy reforms and fair implementation as necessary to tackle corruption. This could include strengthening anti-corruption legislation, ensuring the independence of anti-corruption bodies, and creating a culture of accountability. Encouragingly, international collaborations with agencies that have a zero-tolerance policy towards corruption were seen as a strategy to improve the current practices.

Institutional and legal barriers

Institutional stakeholders in Africa often struggle with limited resources, bureaucratic rigidity, and a lack of clear policies for diaspora engagement. This institutional landscape, shaped by colonial and postcolonial governance structures, can create barriers to effective knowledge transfer and collaboration. As one university administrator noted:

"We recognise the value of diaspora expertise, but our systems are not always flexible enough to accommodate their unique positions. Sometimes, it's a challenge just to create appropriate contractual arrangements for short-term collaborations.

This comment highlights the need for institutional reforms that can better facilitate diaspora engagement, addressing the legacy of colonial-era administrative structures that may not be conducive to modern, transnational collaborations.

Participants highlighted institutional barriers as challenges hindering their contribution. For example, an educator with a decade of experience overseas narrated the arduousness of re-establishing a career back home due to immense bureaucratic barriers. Similarly, a diaspora investor dedicated to the proliferation of rural schools underscores the procedural adversities faced by narrating:

"Securing permits, finding local partners, it is a constant battle. If the processes were smoother, we could do so much more."

The frustration voiced here gestures towards an institutional rigidity that not only debilitates proactive change-makers but also implicitly discredits the qualifications and potential of African diaspora members to propound improvements in their own communities.

Moreover, prevailing colonial-era mobility constraints that affect the diaspora, as discussed by a social entrepreneur looking to invest in impactful local projects, demonstrate the failure of policy frameworks to adapt to the contemporary needs of transnational African professionals. The entrenched vision of diaspora members as 'foreigners', rather than as nationals with vested interests and invaluable contributions, exemplifies how policies remain entrenched in archaic, exclusionary paradigms.

By side-lining African know-how and favouring expatriate expertise, these countries inadvertently perpetuate a cycle of dependency and undermine their own pool of highly skilled professionals eager to contribute to their nation's growth and well-being. African institutions must recalibrate their recognition and integration processes, policies, and perceptions to foster an environment that embraces its diaspora as a critical resource for development and innovation.

Stigma attached to diaspora talent

Beyond institutional and legal barriers, there is a stigma attached to diaspora talent, according to one innovator:

"I have seen a number of my designs being used in my country mainly in telecoms. Those products were supplied by foreign companies I licensed the technologies to and my countrymen embraced the products because they came through foreign companies - Can you imagine? In Africa, we embrace technologies from abroad, yet a number of these products are African brains."

The stigma attached to diaspora talent is particularly discouraging for African innovators who face obstacles in having their work recognised and valued in their home markets. The preference for foreign products, even when local inventors create them, is a manifestation of postcolonial consumer behaviour that devalues local expertise in favour of foreigners, as discussed by Shizha (2010). This attitude undermines the potential for local industry growth and the cultivation of indigenous innovation ecosystems.

To change the stigma against local innovation, participants suggested the need to promote 'Made in Africa' campaigns that highlight local success stories in innovation and embrace innovations by the African diaspora. As one participant commented:

"Do you know that one-third of entrepreneurs/innovators in the USA are foreigners? Our sons and daughters are part of designing teams designing cars at those big car makers, amazing computer programmers, fixing aircraft for major airlines, and pioneering medical solutions."

This acknowledgement of the African diaspora's significant contribution to global innovation speaks to the concept of 'brain gain', where the skills and expertise of those living outside the continent can be leveraged for its development. As highlighted by a participant, many Africans abroad are excelling in various sectors such as technology, automotive, aviation, and medicine. Studies by Nkongolo-Bakenda & Chrysostome (2013) emphasise the valuable contributions of the diaspora to entrepreneurship and innovation in their home countries, should effective engagement strategies be employed.

Participants recommended the establishment of effective knowledge networks that tap into the expertise and talent of the diaspora for innovation, research, development, and education such as think tanks or innovation hubs that are partially manned by professionals from the diaspora. It was also noted that African countries can set up dedicated diaspora offices to provide support to repatriates seeking to start businesses, focusing on proper checks without the intention to intimidate them. Recognising diaspora contributions at national events and through media could also foster a supportive environment.

Scrutiny of Diaspora Endeavours

Participants highlighted instances where successful endeavours are met with scrutiny rather than support. In this regard, some participants felt that there were efforts to “Pull him/her Down” when someone appeared to be doing well. One successful innovator reported:

"We were investigated by all security agencies, many felt threatened by our business. We were questioned about the source of our funds, our partners, other governments, companies we were doing business with, and some rubbished us."

These findings reflect a broader sense of jealousy, scrutiny and scepticism towards the diaspora as observed by Agyeman (2014). For Mercer et al. (2009) these behaviours can sometimes stem from concerns about unequal wealth distribution, neo-colonial influences, or the perceived allegiance of the diaspora members. This cultural dynamic can discourage diaspora engagement and detract from the collaborative potential between local and international African talents.

To address this, participants suggested the establishment of fair legal frameworks that protect entrepreneurs and investors, including those from the diaspora. These frameworks should standardise the scrutiny process to ensure that it is not arbitrarily applied or used to intimidate successful diasporans but is instead part of a routine due diligence that fosters transparency and confidence among all stakeholders. Where these policies are in place participants decried the unfair implementation processes which tended to favour high-profile diaspora figures at the expense of broader diaspora interests.

Enabling Diaspora Engagement

Developing financing mechanisms such as diaspora bonds or investment funds to support diaspora-led projects was suggested. This could include providing tax incentives for diaspora investments, offering matching grants for development projects, or reducing bureaucratic hurdles for business setup and land acquisition. This would go a long way in assisting the diaspora beyond just using them as one participant suggested:

"We need to move beyond seeing the diaspora as just a source of remittances. There's a wealth of knowledge and experience that can transform our institutions if we create the right channels for collaboration."

This perspective aligns with coloniality theory's call for decolonising knowledge structures and recognising the value of diverse epistemologies in driving development.

Participants indicated a deliberate exclusion from participating in key activities and decisions in their home countries, for example, voting. To facilitate active diaspora engagement, participants recommended the development of programs that are sensitive to the needs of diaspora communities. These might include dual citizenship arrangements, voting rights for the diaspora, and formal channels for diaspora members to input into national development plans. Furthermore, the creation of reintegration programs that assist with professional accreditation, recognition of qualifications, and job placement for returning professionals would make the transition smoother for those willing for permanent return. However, a participant from an African institution cautioned:

"When the Diaspora Engagement Committee was established, we were all quite optimistic about its potential to better connect our diaspora community. The Partnership Taskforce seemed earnest in its goals of driving investment, knowledge sharing and cultural exchanges. In the early stages, their efforts led to some notable successes. Investments did flow in and capacity-building programs made valuable contributions. But it soon became apparent that institutional support was wavering."

The participant added that:

![]() After three years, with no advocacy at higher levels and no champions/members from the diaspora, the Taskforce has become an empty shell. This outcome shows we still have far to go in prioritising the diaspora community through concrete long-term support, not just fleeting gestures.

After three years, with no advocacy at higher levels and no champions/members from the diaspora, the Taskforce has become an empty shell. This outcome shows we still have far to go in prioritising the diaspora community through concrete long-term support, not just fleeting gestures.

Constituting diaspora advisory councils must therefore include diaspora leaders and professionals who can provide insight into the needs and expectations of the diaspora community. These members can advise on policy matters and help design frameworks that are considerate of diaspora sentiments and cultural nuances.

Framework for diaspora knowledge democracy

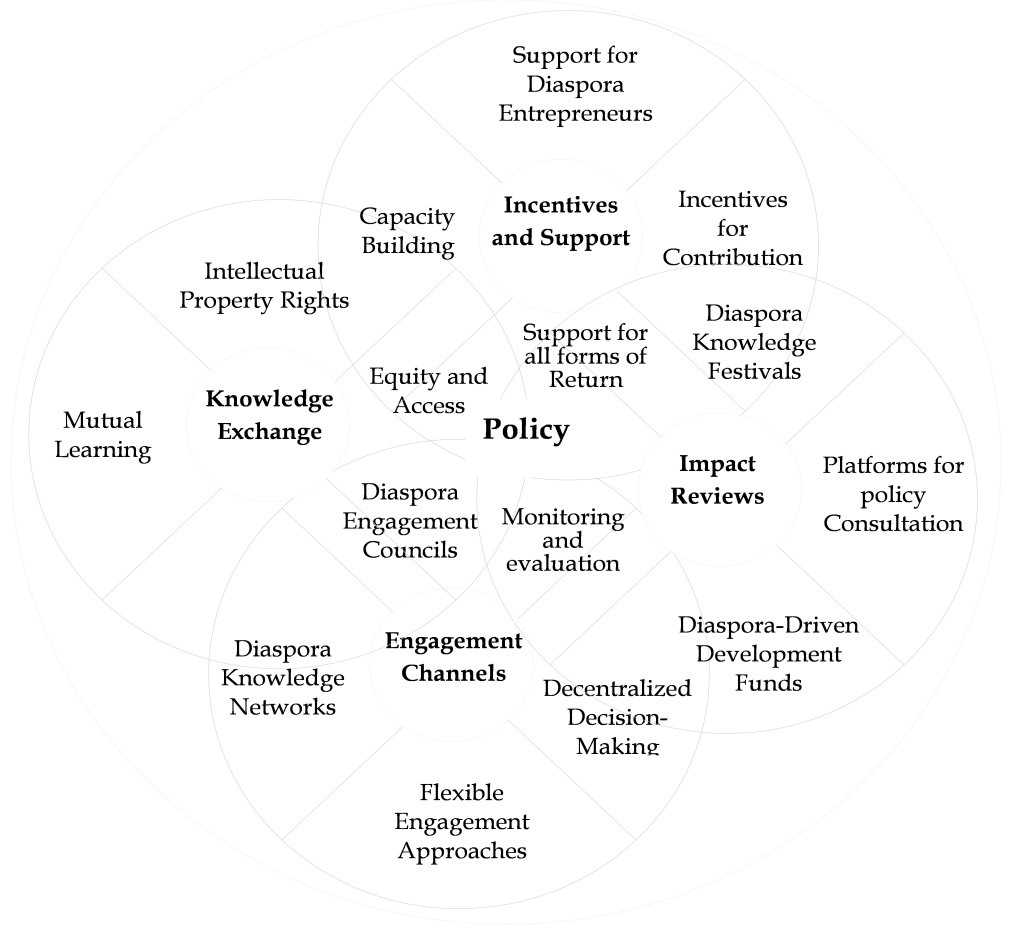

Addressing our final research question, we synthesised the insights from diaspora professionals and African stakeholders to develop a framework for more inclusive and effective diaspora engagement. Figure 1 visually depicts the framework wherein policy is at the core supporting the building blocks namely incentives and support, knowledge exchange, engagement channels, and impact reviews.

Figure 1: Framework for diaspora knowledge democracy

Enabling policies that dismantle colonial divisions through strengthened mobility and participation rights serves as the foundation for dismantling hierarchical structures and empowers diverse voices. Robust engagement platforms facilitate multidirectional knowledge exchange between diaspora communities and stakeholders across Africa fostering collaboration and aligning with the principles of knowledge democracy. The emphasis on diverse voices and collaborative networks aligns well with the concept of knowledge democracy, moving away from hierarchical structures that concentrate power. The emphasis on coordinated incentives and support for diaspora initiatives is key. By bringing together technical expertise from various settings, these initiatives could accelerate work on pressing issues, capture relevant insights on project implementation and scale successes. Regular evaluation would ensure the initiatives remain responsive.

While ambitious, the viability of this framework could be enhanced through pilot testing of individual elements with staggered rollout. For example, launching an initial engagement platform and paired exchange program between select diaspora networks and institutions may surface practical considerations to refine implementation strategies. Securing multi-stakeholder buy-in and identifying sustainable funding mechanisms early also seem prudent to anchor the approach. Diaspora advisory boards and reciprocal short secondments may aid governance and coordination. Overall, properly operationalised, this inclusionary, collaborative model holds promise for catalysing Africa's development trajectory through optimised diaspora participation and knowledge-sharing for the future benefit of all.

This commitment must be rooted in a shared recognition of the diaspora's unique value. Their cultural competencies, technical skills, and experiential knowledge are all essential assets for Africa's self-determined progress.

CONCLUSION

This study set out to explore the lived experiences of diaspora professionals and African institutions using the coloniality lens. Our findings revealed that while individual and institutional efforts have made inroads, there remains a lack of coordinated strategy to maximise diaspora contributions through knowledge democracy. To overcome these challenges, a paradigm shift is proposed, reframing the diaspora as equitable knowledge democracy partners and embracing their expertise and contributions.

The study emphasises the importance of mobilising human capital through bridge-building centred on reciprocal knowledge-sharing. Establishing robust diaspora engagement platforms featuring multi-stakeholder participation can address trust issues and bureaucratic challenges. Recognising diverse contributions through support networks nurturing collaboration between technical professionals, entrepreneurs, scholars, and community groups will catalyse inclusive growth. Addressing corruption and promoting accountability strengthens institutional reliability for investors and partners.

Going forward, a coordinated transnational approach is needed to overcome fragmented efforts and resource constraints. Capacity strengthening initiatives must engage grassroots organisations for widespread impact translating research. Tracking best practices and metrics can optimise programs adapting to complex realities.

Overall, this study calls for reconceptualising diaspora as equitable knowledge democracy partners as central, not peripheral, to development visions. Operationalising inclusive models demanding interactivity between policymakers, institutions, and diaspora communities will build the requisite buy-in and ownership for sustainable progress. Only by dismantling divides and forging unity founded on mutual recognition and benefit can Africa harness its full spectrum of human capital to ignite an inclusive, self-determined trajectory of growth.

REFERENCES

Agunias, D. R., & Newland, K. (2012). Developing a Road Map for Engaging Diasporas in Development: A Handbook for Policy Makers and Practitioners in Home and Host Countries. MPI and IOM.

Agyeman, O. (2014). Power, powerlessness, and globalization: Contemporary politics in the global south. Lexington Books.

Alem, A. (2016). Impact of Brain Drain on Sub-Saharan Africa. The Reporter. Anderson, B. (2019). Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. Verso Books.

Andresen, M., Lazarova, M., Apospori, E., Cotton, R., Bosak, J., Dickmann, M., Kaše, R., & Smale, A. (2022). Does international work experience pay off? The relationship between international work experience, employability, and career success: A 30 country, multi-industry study. Human Resource Management. https://doi.org/10.1111/1748- 8583.12423

Baser, B., & Swain, A. (2008). Diasporas as Peacemakers: Third Party Mediation in Homeland Conflicts. International Journal on World Peace, 25(3), 7–28.

Brinkerhoff, J. M. (2012). Creating an enabling environment for diasporas' participation in homeland development. International Migration, 50(1), 75–95.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101.

Britannica, The Editors of Encyclopaedia. (2024, October 3). "human migration". Encyclopedia Britannica, 3 Oct. 2024, https://www.britannica.com/topic/human-migration

Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. (2024, April 3). Diaspora. Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/ topic/diaspora-social-science

Brubaker, R. (2005). The 'diaspora' diaspora. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 28(1), 1–19.

Carbajal, M. J., & de Miguel Calvo, J. M. (2021). Factors that influence immigration to OECD member States. Cuadernos de Trabajo Social, 34, 417–430. Gale Academic OneFile. https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/A669165126/ IFME?u=anon~fda

Castles, S., de Haas, H., & Miller, M. J. (2013). The Age of Migration: International Population Movements in the Modern World. Guilford Press.

Chikanda, A., Crush, J., & Walton- Roberts, M. (Eds.). (2016). Diasporas, development and governance. Springer International Publishing.

Cooper, F. (2005). The Rise, Fall, and Rise of Colonial Studies. In Colonialism in Question: Theory, Knowledge, History. Berkeley: University of California Press, pp. 33–55.

Creswell, J. W., & Poth, C. N. (2018). Qualitative Inquiry S Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches (4th ed.). Sage Publications.

Docquier, F., & Rapoport, H. (2012). Globalization, brain drain, and development. Journal of Economic Literature, 50, 681-730.

Dufoix, S. (2011). From Nationals Abroad to ‘Diaspora’: The Rise and Progress of Extra-Territorial and Over-State Nations. Diaspora Studies, 4(1), 1-20. https://brill.com/ search? q=DUFOIX&source=%2Fjournals%2Fbdia%2Fb dia-overview.xml

Dussel, E. (1995). The Invention of the Americas: Eclipse of the Other and the Myth of Modernity. New York: Continuum.

Edeh, E. C., Osidipe, A., Ehizuelen, M. M. O., & Zhao, C. C. (2021). Bolstering African strategy for sustainable development and its diaspora’s influence on African development renaissance. Migration and Development. https://doi.org/10.1080/21632324.2020.1855737

Edeh, E. C., Zhao, C. C., Osidipe, A., & Lou, S. Z. (2023). Creative approach to development: Leveraging the Sino-African Belt and Road Initiatives to boost Africa's cultural and creative industries for Africa's development. East Asia, 40(1), 1-19. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12140-022-09388-z

Elabor-Idemudia, P. (2011). Identity, Representation, and Knowledge Production. Counterpoints, 379, 142–156. http://www.jstor.org/stable/42980891

Gamlen, A. (2006). Diaspora Engagement Policies: What Are They, and What Kinds of States Use Them? Centre on Migration, Policy and Society Working Paper No. 32, University of Oxford.

Gevorkyan, A. V. (2022). Diaspora and Economic Development: A Systemic View. The European Journal of Development Research, 34, 1522–1541. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41287-021-00432-x

Gnimassoun, B., & Anyanwu, J. (2019). The Diaspora and Economic Development in Africa. Review of World Economics, 155. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10290-019-00344-3

Grosfoguel, R. (2007). The epistemic decolonial turn: Beyond political-economy paradigms. Cultural Studies, 21(2-3), 211-223.

Grosfoguel, R., 2011. Decolonising Post-Colonial Studies and Paradigms of Political Economy: Transmodernity, Decolonial Thinking and Coloniality. Journal of Peripheral Cultural Production of the Luso- Hispanic World. 1(1):1-5.

Grosfoguel, R. (2013). The structure of knowledge in Westernized universities: Epistemic racism/sexism and the four genocides/epistemicides of the long 16th century. Human Architecture: Journal of the Sociology of Self-Knowledge, 11(1), 73-9.

Haraway, D. (1988). Situated knowledges: The science question in feminism and the privilege of partial perspective. Feminist Studies, 14(3), 575-599.

Kessi, S., Marks, Z., & Ramugondo, E. (2020). Decolonizing African Studies. Critical African Studies, 12(3), 271–282. https://doi.org/ 10.1080/21681392.2020.1813413

Khalid, B., & Urbański, M. (2021). Approaches to understanding migration: A multi‐country analysis of the push and pull migration trend. Economics and Sociology, 14(4), 249–274. http://dx.doi.org/10.14254/2071-789X.2021/14-4/14

Knittel, B., Coile, A., Zou, A., Saxena, S., Brenzel, L., Orobaton, N., Bartel, D., Williams, C. A., Kambarami, R., Tiwari, D. P., Husain, I., Sikipa, G., Achan, J., Ajiwohwodoma, J. O., Banerjee, B., Kasungami, D. (2023). Critical barriers to sustainable capacity strengthening in global health: a systems perspective on development assistance. Gates Open Research, 6:116. https://doi.org/10.12688/ gatesopenres.13632.2

Kopchick, C., Cunningham, K. G., Jenne, E. K., & Saideman, S. (2022). Emerging diasporas: Exploring mobilization outside the homeland. Journal of Peace Research, 59(2), 107-121.

Kuznetsov, Y. (2006). Diaspora Networks and the International Migration of Skills: How Countries Can Draw on Their Talent Abroad. Washington DC: World Bank Publications.

Langa, P. V. (2018). African Diaspora and its Multiple Academic Affiliations: Curtailing Brain Drain in African Higher Education through Translocal Academic Engagement. Journal of Higher Education in Africa / Revue de l’enseignement Supérieur En Afrique, 16(1/2), 51–76. https://www.jstor.org/ stable/26819628

Levitt, P., & Jaworsky, B. N. (2007). Transnational migration studies: Past developments and future trends. Annual Review of Sociology, 33, 129-156.

Madziva, R., Thondhlana, J., Garwe, E. C., Murandu, M., Chagwiza, G., Chikanza, M., and Maradzika, J. (2021). Internally displaced persons and COVID-19: a wake-up call for and African solutions to African problems – the case of Zimbabwe. Journal of the British Academy, 9(s1), 285–302. https://doi.org/ 10.5871/jba/009s1.285

Maldonado-Torres, N. (2007). On the coloniality of being: Contributions to the development of a concept. Cultural Studies, 21(2-3), 240-270.

Mamdani, M. (1996). Indirect rule, civil society, and ethnicity: The African dilemma. Social Justice, 23(1/2 (63-64)), 145-150.

Martin, P. L., & Papademetriou, D. G. (1991). The unsettled relationship: Labor migration and economic development. Population and Development Review, 17, 743.

Mercer, C., Page, B., & Evans, M. (Eds.). (2009). Development and the African diaspora: Place and the politics of home. Zed Books.

Mbembe, A. (2017). Critique of Black Reason. Duke University Press.

Mignolo, W. D. (2011). Geopolitics of sensing and knowing: on (de)coloniality, border thinking and epistemic disobedience. Postcolonial Studies, 14(3), 273–283. https://doi.org/10.1080/13688790.2011.613105

Mohanty, C. T. (1984). Under Western Eyes: Feminist Scholarship and Colonial Discourse. Boundary 2 (12) 3: 333–58.

Ndlovu-Gatsheni, S. J. (2015). Decoloniality as the future of Africa. History Compass, 13(10), 485-496.

Ndlovu-Gatsheni, S. (2018). Dynamics of epistemological decolonisation in the 21st century: Towards epistemic freedom. Strategic Review for Southern Africa, 40(1):16-45.

Nkongolo-Bakenda, J.M. & Chrysostome, E. (2013). Engaging diasporas as international entrepreneurs in developing countries: In search of determinants. Journal of International Entrepreneurship, Springer, 11(1): 30-64. Nelson.

Nkrumah, K. (1965). Neo-colonialism.

Olayiwola, J. N., Udenyi, E. D., Yusuf, Shizha, E. (2010). Rethinking and reconstituting indigenous knowledge and voices in the academy in Zimbabwe: A decolonization process. In Indigenous G., Magaña, C., Patel, R., Duck, B., & Kibuka, C. (2020). Leveraging electronic consultations to address severe subspecialty care access gaps in Nigeria. Journal of the National Medical Association, 112(1), 97-102.

Prakash, G. (1995). Introduction: After Colonialism: Imperial Histories and Postcolonial Displacements, (Prakash, G, Ed) Princeton: Princeton University Press, pp. 3-18. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781400821440.3

Pratt, B., & de Vries, J. (2023). Where is knowledge from the global South? An account of epistemic justice for a global bioethics. Journal of Medical Ethics, 49(5), 325-334. https://doi.org/10.1136/jme-2022-108291.

Quijano, A. (2007). Coloniality and modernity/rationality. Cultural Studies, 21(2- 3), 168-178.

Rustomjee, C. (2018). Issues and challenges in mobilizing African diaspora investment. Policy Brief No. 130, 25 April. The Centre for International Governance Innovation.

Shaw, J. (2021). Citizenship and COVID-19: Syndemic Effects. German Law Journal, 22(8), 1635-1660. https://doi.org/ 10.1017/glj.2021.77

Shin, J., Seo, M., & Lew, Y. K. (2022). Sustainability of digital capital and social support during COVID-19: Indonesian Muslim diaspora’s case in South Korea. Sustainability, 14(12), 7457.

Spivak, G. C. (1988). Can the subaltern speak? In C. Nelson S L. Grossberg (Eds.), Marxism and the Interpretation of Culture (pp. 271-313). University of Illinois Press. Knowledge and Learning in Asia/Pacific and Africa: Perspectives on Development, Education, and Culture (pp. 115-129). Palgrave Macmillan US.

Thondhlana, J., Madziva, R., & McGrath, S. (2016). Negotiating employability: Migrant capitals and networking strategies for Zimbabwean highly skilled migrants in the UK. The Sociological Review, 64(3), 575-592.

Thondhlana, J., & Madziva, R. (2018). Skilled Migrant African Women of Faith and Diaspora Investment. In D. Hack-Polay S J. Siwale (Eds.), African Diaspora Direct Investment: Economic and Sociocultural Rationality (pp. 239-264). Palgrave Macmillan.

Walsh, C. 2013. Pedagogías decoloniales. Insurgent practices of resistir, (re)existir and (re)vivir. Quito: Abya Yala: 24.

Zanabazar, A., Kho, N. S., & Jigjiddorj, S. (2021). The push and pull factors affecting the migration of Mongolians to the Republic of South Korea. Presented at the SHS Web of Conferences, České Budějovice, Czech Republic, November 19, vol. 90, p. 01023.

Zeleza, P. T. (2013). Engagements between African Diaspora Academics in the U.S. and Canada and African Institutions of Higher Education: Perspectives from North America and Africa. Report for the Carnegie Corporation of New York.

Zeleza, P. T. (2019). Leveraging Africa’s Global Diasporas for the Continent’s Development. African Diaspora, 11(1-2), 144-161. https://doi.org/10.1163/18725465-01101002