Introduction

Globally, policymakers, researchers, citizens, and non-state actors have been increasingly focused on understanding the nuances and complexities of financial inclusion (FI) and its understated impact on fostering inclusive economic and social development, especially in developing countries such as Zimbabwe (World Bank, 2022). While there is no single or homogenous definition of FI, there is a consensus on the core premise of the concept which involves the degree of access of households and firms, especially poorer households, and micro, small and medium-sized enterprises (MSMEs), to financial services (Yoshino & Morgan, 2016; United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, 2022). Studies on development challenges faced by developing countries indicate a common trend of inequitable and disproportionate access to inclusive financial resources as a core obstacle to social-economic development prospects in these countries (Ngonyani, 2022; World Bank, 2022; Isukul, Agbugha, & Chizea, 2019). The World Bank estimates that at least one third of adults in the world are excluded from mainstream formal financial and non-banking intermediaries (World Bank, 2022). A vibrant, financially inclusive environment is a pre-requisite for poverty reduction and the growth of productive sectors of the economy (Isukul et al, 2019). The absence of a coherent, empowering and inclusive financial service supportive framework has significant repercussions for citizens' livelihoods and economic agents such as MSMEs. Hence the need for ongoing reflections on the state of financial inclusion in countries such as Zimbabwe which have significant economic and social development challenges.

Synopsis of Financial Inclusion in Zimbabwe

Zimbabwe has been a part of the Alliance for Financial Inclusion since 2012, a network of policy-making bodies and central banks from over 80 emerging and developing market economies. This network gives Zimbabwe access to the latest policies and programs related to financial inclusion. Various studies by civic organisations and economic think tanks have been commissioned to study the FI landscape in Zimbabwe over the last decade. Key studies include the Zimbabwe Economic Policy Analysis and Research Unit (ZEPARU) study in 2011, a study by Baragahara in 2021, FinScope MSME studies in 2012, a study by FinMark Trust in 2014 and the Acacia Economics study in 2020. These studies have covered diverse issues such as the barriers to FI and the policy framework supporting FI in Zimbabwe. Thus, our study is well positioned to reflect on the progress made to date in attempts to enhance FI in Zimbabwe.

The Government of Zimbabwe (GoZ), through the Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe, has been the principal custodian of the National Financial Inclusion Strategy, which commenced with the introduction of a four-year National Financial Inclusion Strategy (NFIS) in 2016 (Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe, 2016). In this strategy, a definition for FI is outlined as "the effective use of a wide range of quality, affordable and accessible financial services provided fairly and transparently through formal, regulated entities by all Zimbabweans" (RBZ, 2016, p. 15). The key overarching goal of the 2016 NFIS was to improve FI through targeted interventions focusing on enhancing access (from 69% to 90% by 2020) for women, youth and people living with disabilities, increasing the proportion of banked adults from 30% in 2014 to at least 60%. A summary evaluation of the successes of the NFIS is outlined in later sections of this paper.

The purpose of the study is to investigate the successes, gaps, limitations and failures of initiatives to improve FI in Zimbabwe and its potential impact in achieving inclusive socio–economic development that is citizen-centred. Our study contributes to the limited understanding about the successes, limitations and failures of FI initiatives in Zimbabwe. We contextualise the narrative on FI in Zimbabwe from the context of the country's nuanced complexities and lack of political goodwill. We then advocate for a new thinking of what should frame the narrative on FI, outlining expanded value-adding policy interventions.

The study is structured as follows, first, a summary of literature on various aspects of FI to explain the research gaps, followed by an outline of the methodology used for the study, findings and discussion. The second part of the paper addresses the paradox of the Zimbabwean nuances and complexities; political stakeholder dilemma and an outline of a framework for new thinking for Financial Inclusion in Zimbabwe and policy recommendations.

Literature Review

Conceptualising Financial Inclusion

There are a variety of definitions of the FI concept and its measurable indices (Isukul & Dagogo, 2018; Kumar, 2017; Mahmood, Shuhui, Aslam, & Ahmed, 2022). One critical school of thought on FI focuses on promoting affordable, timely and adequate resources to a diverse ecosystem of regulated financial products and services that can be used by different groups in society (Atkinson and Messy, 2013). Besides access and affordability, this lens on FI advocates for the integration of supporting mechanisms such as financial literacy education and impact on socio-economic development. The other emerging school of thought focuses on the extent or degree of access to financial services by poorer households and MSMEs (Yoshin & Morgan, 2016). The United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) defines FI based on the percentage of adults, 15 years old and above, who reported having at least one account in their name with an institution that provides financial services which are subject to some form of government regulation (UNCTAD, 2021).

Financial Inclusion and Social-economic Development

There is consensus on the established correlation between FI and socio-economic development. Some scholars (Brown, Mackie, Smith, & Msoka, 2015; Oshora, Desalegn, Gorgenyi-Hegyes, Fekete-Farkas, & Zeman, 2021) posit that FI positively influences economic growth levels and reduces income inequality in society. This influence is intermediated through financial development, accelerated business investment, and increased productivity by crucial economic growth drivers such as MSMEs (Villarreal, 2017). Other studies provide evidence of the impact of FI on socio-economic development in developing countries through equitable and expansive re-distribution of economic opportunities which empower marginalised groups such as rural citizens and women (Ahmed & Wei, 2014; Isukul & Tantua, 2021). Lack of implementable and inclusive financial policies is likely to result in MSMEs and entrepreneurs resorting to informal practices which could negatively impact economic output crucial to social–economic development (Krumer-Nevo, Gorodzeisky, & Saar-Heiman, 2017; Were, Odongo & Israel, 2021).

Characteristics of Financial Inclusion & Barriers

There is an established body of cross-disciplinary literature on the diverse nature of barriers to FI for MSMEs and households. However, these continue to evolve, hence the need for continued research in different emerging contexts such as Zimbabwe (Isukul & Tantua, 2021). Common factors driving FI include reliable, established supportive institutions supported by efficient judicial systems, the rule of law, and general political stability (Guitierrez-Neto, Serrano-Cinca, Cuellar-Fernández, & Fuertes-Callén, 2017). There is an established portfolio of barriers comprising demand-side, supply-side, regulatory, and infrastructure factors. Women and other disadvantaged groups such as the disabled are more likely to be affected by these barriers than other groups.

In Africa, it is estimated that 4 out of 5 women lack access to financial services (Ngonyani, 2022). Examples of demand-side barriers include financial illiteracy, lack of collateral and knowledge of financial products. Infrastructure and regulatory obstacles such as weak policies, stringent anti-poor regulations, and weak government support are common barriers in developing countries (Isakul et al., 2019; Ngonyani, 2022). The manifestation and impact of these barriers are different across countries due to each country's nuances and complexities, hence the importance of current research. Our study on Zimbabwe becomes even more crucial as Zimbabwe is one country that is undergoing various economic cycles that have changed its social and economic development narrative.

Financial Inclusion Interventions

Various interventions have been introduced to foster FI in many African countries using National Financial Inclusion Strategies (Isakul et al., 2019; Ngonyani, 2022; Triki & Faye, 2013). However, as with other national programmes, there is no shortage of well-documented national strategies to enhance FI. Key success measures of interventions in Tanzania include the impact of new digital technology on expanding mobile money transfers, savings and diverse payment transactions that have translated to growth of businesses. The Alliance for Financial Inclusion and National Financial Inclusion Framework report indicates noticeable evidence of improved access to financial services in Tanzania (Ngonyani, 2022).

Nevertheless, there is always the question of whether these strategies have been effectively implemented with the intended impact and outcome, especially for groups such as women and MSMEs. Shared best practice interventions include increasing innovative financial products and services powered by digital capabilities such as mobile telephony (Demirgüç-Kunt & Klapper, 2012). The rapid penetration of mobile telephony has improved access to some form of financial services to the vast majority at the bottom of the pyramid of unbanked consumer groups in Africa. Has this been the panacea to the lack of financial inclusion, and to what extent has this changed the levels of financial inclusion for these groups? Further questions relate to how continued political and economic uncertainty in countries such as Zimbabwe has diminished the potential impact of these new financial services delivery technologies.

Methodology

The study is based on a mixed methods approach comprising two phases. The first phase involved primary data collection using a national survey administered through face-to-face interviews with MSMEs. The second phase involved a secondary data-based review of institutional studies on financial inclusion in Zimbabwe by critical stakeholders such as the Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe (RBZ) and FinMark Trust.

Sampling

Data was collected from 1,402 small enterprises from the ten administrative provinces of Zimbabwe, broken down into 60 micro, 40 small and 20 medium enterprises. Convenience sampling was used to recruit participants. Our sampling also targeted distribution of 63% in rural areas and 37% in urban areas. This target was based on data from ZIMSTAT findings on the percentage distribution of MSMEs in rural and urban areas in Zimbabwe. We used the classification of MSMEs according to the Ministry of Women's Affairs, Community, Small and Medium Enterprises Development in Zimbabwe (MWSMED) to identify the target enterprises for the survey. Data was collected in September and October 2021 using trained enumerators stationed in the ten provinces. Table 1 is a summary of the profile of MSME participants.

Table 1: Profile of Participants

| Category | Element | # | % |

| Total | Respondents | 1402 | 100% |

| Enterprise Size | Micro | 995 | 71% |

| Small | 361 | 26% | |

| Medium | 46 | 3% | |

| Age | 18 to 25 | 90 | 6% |

| 26 to 35 | 428 | 31% | |

| 26 to 45 | 548 | 39% | |

| 46 to 65 | 309 | 22% | |

| 66+ | 27 | 2% | |

| Gender | Female | 615 | 44% |

| Male | 787 | 56% | |

| Province | Bulawayo | 128 | 9% |

| Harare | 155 | 11% | |

| Manicaland | 151 | 11% | |

| Mashonaland Central | 111 | 8% | |

| Mashonaland East | 132 | 9% | |

| Mashonaland West | 162 | 12% | |

| Masvingo | 154 | 11% | |

| Matabeleland North | 144 | 10% | |

| Matabeleland South | 139 | 10% | |

| Midlands | 126 | 9% | |

| Location | Urban | 725 | 52% |

| Rural | 677 | 48% | |

| Sector | Retail and wholesale | 306 | 22% |

| Vending (tuck-shop/flea market) | 299 | 21% | |

| Agriculture, hunting, forestry and fishing. | 150 | 11% | |

| Catering, baking and culinary arts | 73 | 5% | |

| Trichology and cosmetology | 63 | 4% | |

| Tourism accommodation and restaurants | 52 | 4% | |

| Logistics and transport | 50 | 4% | |

| Mining and quarrying | 48 | 3% | |

| Textile, apparel, leather | 46 | 3% | |

| Construction, energy, water and architecture | 43 | 3% | |

| Manufacturing | 39 | 3% | |

| Information and communication technology | 35 | 2% | |

| Graphics, technical design, software and printing | 30 | 2% | |

| Professional, consulting, scientific and technical activity | 23 | 2% | |

| Handicrafts | 20 | 1% | |

| Education | 20 | 1% | |

| Health and social services | 17 | 1% | |

| Arts, culture, sport, events, media, and entertainment | 17 | 1% | |

| Financial services and insurance | 11 | 1% |

Data Analysis

Data analysis from the survey comprised analysis of descriptive statistics supported by qualitative thematic content analysis of the responses. Data from the secondary data-based studies was analysed primarily using qualitative content techniques. Analysis of the meaning of the text was carried out through condensation, categorisation, narration and interpretation.

FINDINGS AND DISCUSSIONS

To address our research gaps, we separate our findings into two parts. The first part looks at the prima-facie analysis or evaluation of the NFIS's impact on addressing the barriers identified in the literature based on the available secondary data. The second part of our findings focuses on establishing the perceptions of the intended target beneficiaries of the NFIS, such as women and MSMEs. This sets a foundation for a balanced evaluation of the extent to which the government and other stakeholders in Zimbabwe have made progress in promoting FI against the backdrop of the NFIS strategy. This empirical data provides insights on whether the stated accomplishments of the NFIS are reflective and representative of the experience of citizens and MSMEs on the ground.

The NFIS Interventions and Accomplishments

Policy Environment

The GoZ has put policies and legislative instruments that cover various aspects of FI. These are outlined in Annex 1. The RBZ, through the NFIS, is the principal custodian of strategy and policy formulation for financial inclusion-related interventions. The Central Bank continues to work with mainstream financial services providers to improve areas such as consumer protection and women empowerment.

Access Evaluation

The Making Access Possible Study by Acacia highlights that Zimbabwe has achieved the targets set out in the 2016 Financial Inclusion Strategy (NFIS 2016–2020) due to the increased proportion of banked adults to at least 60% and access to affordable and appropriate financial services to 90% based on mobile money penetration (Acacia, 2020). The advent of mobile money has improved access to financial services for consumers in both rural and urban areas. Nonetheless, there remains some barriers to this channel due to limited capabilities. Key barriers include limited access to mobile networks in some areas, high cost of mobile data, poor digital literacy and prohibitive taxes associated with mobile money transactions. However, this is a narrow lens on what constitutes FI beyond just mobile money, particularly if one evaluates the realities of whether targeted beneficiaries such as MSMEs and women utilise mobile money as their crucial mechanism to participate in the financial services ecosystem. Moreover, there is a need to reflect on the restrictions and constraints of mobile money. For example, the 2% Intermediary Money Transfer Tax has become a barrier to access for most low-income consumers with only transactions under US$5 being exempt (Orbitax, 2022). We found that 18 to 20% of MSMEs in Zimbabwe that do not have access to bank accounts attribute not having an account to high charges. (Chaora, 2022, SIVIO Institute, 2022). Our study addresses the information gap regarding the holistic determination of inclusion through a more inclusive and deep investigation of FI efforts in Zimbabwe.

MSME Promotion and Loan Cover

Regarding enterprise promotion, the value of loans made available to MSMEs has grown from ZWL $131.6 million in 2016 to ZWL$2,03 billion in September 2020 (US$4.25 million to US$6.2 million). The financial inclusion efforts have seen an increase in MSME accounts in the same period, from 71,730 to 142,237 accounts opened. An SME's Forex Exchange was introduced in August 2020. Its purpose is to make foreign currency more readily accessible to MSMEs in order to reduce the reliance on the parallel market (Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe, 2020). However, the SME Forex Auction has had a minimal impact as only 7% of MSMEs are registered on it. Forty percent (40%) of unregistered enterprises state that they have no knowledge of the auction system and 15% say it is irrelevant (Chaora, 2022) since the enterprises need cash to transact and it takes time to gain access to funds in the SME auction and the funds will be electronic when they are finally accessed.

Women Empowerment

The NFIS took the inclusion of women seriously, and 12 out of 19 banking institutions established women's desks in December 2019 to improve women's experience throughout the banking process. According to Acacia Economies (2020) the number of women owning bank accounts increased from 769,883 in December 2016 to 2,536,558 in June 2020. The value of loans to this group also increased from ZWL$277.3 million to ZWL$1.18 billion (Chaora, 2022). As a result, 31.1% of all loans had been given to women. From our study, only 22% of women-led MSMEs with bank accounts indicated that they had applied for a commercial loan where only 8% of rural women-led MSMEs applied, compared to 24% of urban-based women-led MSMEs.

Beyond The Policy Transformation, What Are The Realities On The Ground For The Targeted Beneficiaries?

While the NFIS has introduced various policies and regulations that, in principle, create an environment that addresses some of the barriers, it is imperative to evaluate whether these changes have translated into an impactful difference in the demand and supply side barriers to FI. Is the positive outlook from the policy and regulatory interventions reflective of the extent to which the targeted beneficiaries, especially women and MSMEs, have become integrated into Zimbabwe's financial services ecosystems? Do these stakeholders share the same positive perception of the impact of these interventions on their livelihoods? Further introspection on the extent to which these interventions have collectively translated into socio-economic development provides a more holistic assessment of FI in Zimbabwe based on the actual lived experiences of the intended beneficiaries. By addressing whether there are still any barriers to FI for the targeted beneficiaries, we can develop a balanced assessment of the impact of the regulatory interventions introduced by the GoZ and RBZ. In so doing, a more balanced and nuanced evaluation of the state of FI can be framed.

Demand Side Barriers

Limited Financial Capabilities-Asset Ownership

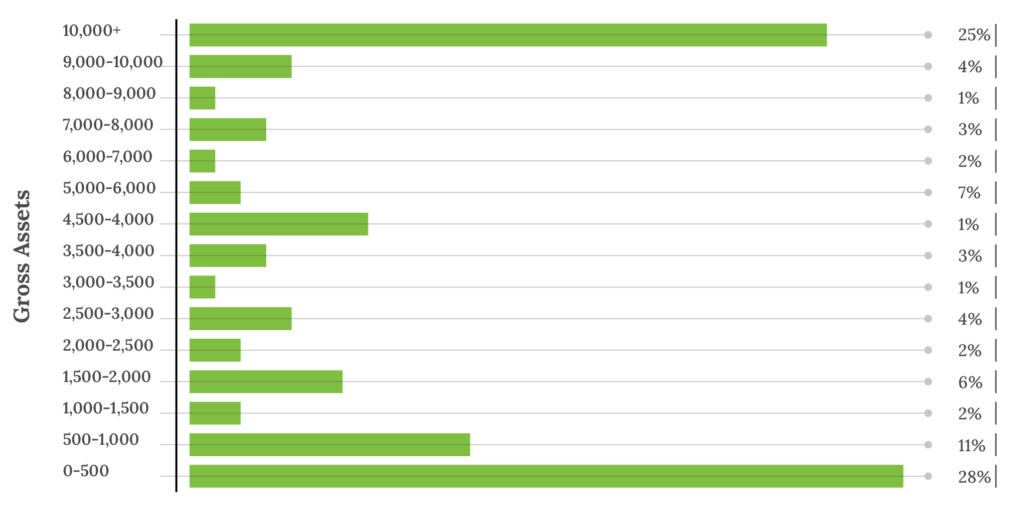

Our findings confirmed the low levels of asset ownership among MSMEs with variations across the different formats. The average gross value of the micro-enterprises is US$3,368.00 for small enterprises, the average gross value of assets is US$41,975.00 and that for medium enterprises is US$306,096.00. Up to 41% (n=574) of enterprises have assets valued at less than US$1,500.00. Lack of 'bankable' assets is recorded in recent literature (Ngonyani, 2022) as a key barrier for MSMEs and individuals to accessing formal financial services that require collateral for access to loans.

Lack of Trust

Lack of trust in the financial services ecosystem and regulatory environment is also a major barrier. This was primarily influenced by Zimbabwe's historical context of hyper-inflationary periods which resulted in citizens losing value in their savings and investments, such as a pensions, deposits and savings. This was partly fuelled by uncertainty in implementing government interventions on savings and currency conversions to manage inflation. The US dollar has been the preferred currency due to its stability. This context has created a level of mistrust of formal financial services since they are the custodians and vehicles for implementing these currency interventions. Most citizens and enterprises do not trust the formal financial system to secure the value of their money. As a result, they opt to operate on a cash basis and not keep money circulating in the formal financial system.

Financial Illiteracy

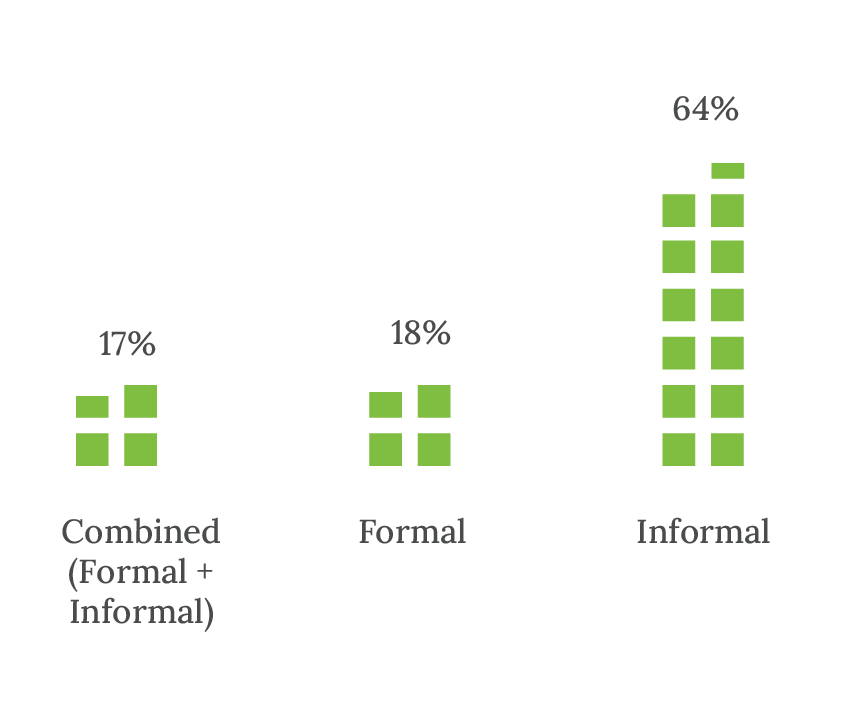

A common theme from respondents and secondary data is the lack of awareness and education on the engagement of financial products and services and the associated complications of processes such as completing loan applications. Access to information and knowledge of financial products determines, to a considerable extent, the quality and success of financial decisions made on behalf of an enterprise or individual. This is likely to be easily facilitated by formal financial advisors, but these were not within reach of both MSMEs and individuals. For example, most enterprises (64%) relied on informal sources of information on financial products since they relied on familial networks to access finance.

There was a general lack of knowledge of the diversity of formal financial products, although levels improved on mobile money services. This confirms an established finding from Ngonyani (2022) and from studies undertaken a decade ago. There were variations in the levels of financial illiteracy based on gender and the rural–urban divide. While an average of 5% of men identified that they do not know anything about the specified financial products and services, 10% of women indicated that they do not know anything. While 35% of urban-based enterprises indicated either a good or very good understanding of financial products, 29% of rural-based enterprises indicated the same. This further exposes women and rural communities to higher levels of exclusion from formal financial ecosystems.

Supply–Side Barriers

Financial Services Operational Barriers

(a) Access to Financial Services

Access to financial services emerges as a critical barrier for MSMEs, particularly for women and those in rural areas. Only 36% of all enterprises interviewed have access to a bank account. The remaining 64% had different reasons for not having bank accounts. The most significant reason for micro-enterprises not having an account is non-registration, indicating that although an enterprise may want an account, they have not followed all the processes that allow access to one. Other reasons mentioned as significant by micro-enterprises include high bank charges (18%) and the perception by many founders that there are not enough security protocols to safeguard their money in the bank (14%). Micro enterprises also gave the reasons that the bank account opening process takes too long, the banks are too far, and they do not have the documentation required by banks.

These factors become magnified when considering the context of the rural areas. In the rural areas, only 23% of enterprises have access to bank accounts, whilst that number rises to 48% in the urban areas. Regarding gender perspectives, women-led enterprises were more likely not to have access to bank accounts. Seventy-five per cent (75%) of women-led enterprises do not have access to bank accounts, while 55% of men-led enterprises did not. It is essential to highlight the reported progress in terms of increases in loan values to women led MSMEs between 2016 and 2019 and the achievements in the banking sector on the empowerment of women highlighted earlier (Acacia Economies, 2020); RBZ, 2020). Nonetheless, significant gender gaps continue to be present. Women with no access cited the following reasons for lack of access: 27% indicated they do not have bank accounts because their businesses are not legally registered, whilst 22% cannot afford a bank account, and 17% reinforced the lack of trust in the system to retain their money safely. Mobile phones and financial technology have improved access rates to financial products and services. More than half (58%) of enterprises in rural and urban areas have a mobile money account.

(b) Funding Sources

There is evidence of low levels of access to funding from formal institutions. Personal savings were the primary source of financing; eighty per cent (80%) of founders used their savings to start their businesses, 7% used banks and 6% used microfinance institutions to secure funding. Respondents relied on personal and familial networks instead of formal financial services to raise funds. For example, 11% of the respondents secured funds from family and friends to finance their start-ups, while 11% secured funding from income savings and lending groups. Only 14% of small enterprises in Zimbabwe make loan applications to formal entities like banks or microfinance institutions with the hope of receiving funding. Respondents reported difficulties in accessing loans citing various reasons. At least 36% said that loan services were unavailable from the bank. The services may have been available to other customers but not to them as individuals.

Other founders noted that they did not have sufficient information on how to make the application, whilst 11% had insufficient documentation, 6% had no collateral or were wary of high-interest rates associated with loans in Zimbabwe. Primary reasons included high inflation and lack of trust in the system. Notably, 30% had their applications rejected because they had not demonstrated a strong cash flow, 25% did not meet the criteria for assets or collateral, 16% had incomplete paperwork, and 6% had not been in business long enough to demonstrate a viable enterprise. Our findings expand the scope of understanding of the challenges MSMEs face in accessing funding beyond the collateral narrative covered by previous studies on FI in Zimbabwe. Zimbabwe is ranked 67th out of 190 countries in terms of low access to credit for MSMEs (Acacia Economies, 2020).

(c) Regulation and Infrastructure

Access to formal financial institutions was closely linked to the registration status of the enterprises. There were more (52%) unregistered enterprises than registered ones. Regarding the perception of registration, up to 89% of the respondents indicated that they felt some form of restriction to compliance. There were diverse reasons for not registering. The overarching reasons were centred on the inconvenience of bureaucracy and lack of awareness. When asked why they had not registered, 39% indicated that they felt the process was bureaucratic, and up to 17% did not know how to get their business registered. Other key reasons were the high registration costs and lack of simplicity and accuracy in the company registration law. Our findings are supported by other significant studies on FI in Zimbabwe, such as Acacia Economies (2020)'s study, which reinforces the negative impact of compliance challenges.

Concerning the gender-registration nexus, it was seen that most unregistered entities are run by women, constituting 54%, while men lead 46%of unregistered entreprises. This compounds the other established barriers to formal financial institutions that account for the lack of FI. Although the introduction of mobile money has improved access to some forms of formal financial products, this has not necessarily been inclusive. There are still some infrastructure gaps and differences in gender distribution. Enterprise founders/owners in rural areas experienced more restrictions (57%) on mobile money use, whilst 53% of enterprise founders in urban areas experienced such restrictions. MSMEs' restrictions include high bank charges, lost or incorrectly billed transactions and mobile devices being incompatible with the mobile money applications. Further reasons for not using mobile money include lack of trust in the system itself and the fact that their business only handles cash transactions, thereby rendering mobile payments irrelevant.

The Paradox of Zimbabwe's Nuances and Complexities

The above findings of the state of FI from the perspective of targeted beneficiaries are closely associated with the nuances and complexities of Zimbabwe's context in the last decade or so. The country's economy has experienced significant structural changes and consequent economic instability and challenging livelihoods for citizens. The economic decline manifested by de-industrialisation, unstable monetary and fiscal environment and hyper-inflation has impacted on citizens’ livelihoods. Most of Zimbabwe's population lives at the periphery of the formal economy; they are either engaged in smallholder agriculture or informal sector activities (sometimes sanitised as MSMEs). The de-industrialisation has resulted in the decline of large formal corporates and the growth of MSMEs in agriculture, vending, retail and the service sectors making the MSME sector a considerable contributor to GDP (60%). (African Development Bank, 2011; Chaora, 2022; International Labour Organisation, 2021).

However, due to the high level of informality, these MSMEs are primarily excluded from the mainstream financial ecosystems, as evident from findings from this study. According to the SIVIO Institute Financial Inclusion Index (SI-Findex), 56% of MSMEs are financially excluded in Zimbabwe. Although there has been some growth in the total loans to MSMEs, these represent approximately 5% of all banking sector loans and advances in 2020 (Acacia Economies, 2020). As of 22 July 2022, a total of US$1.2 million had been disbursed to SMEs through banks and microfinance institutions as part of the COVID-19 support mechanism (RBZ, 2022). This presents an interesting paradox in the narrative on improving FI for MSMEs and citizens in Zimbabwe because there have been insignificant changes in barriers faced by MSMEs and citizens.

High Poverty Levels

A significant hindrance to FI is the state of the Zimbabwean economy itself. Seventy-one (71%) of the population in Zimbabwe live below the total consumption poverty line of US$70 per person per month (upper line), according to the 2017 Poverty, Income, Consumption, and Expenditure Survey. Incomes are low at an average of US$230/month across the employment spectrum, with MSMEs paying as little as US$138/month and state-owned enterprises paying as little as US$183/month (BDEX, 2022). Such low incomes limit the buying power and financial liquidity of households. This is exacerbated by poor prospects for employment in the formal sector.

Inflation and Consumer Confidence

Zimbabwe's high levels of inflation undermine FI gains. Zimbabwe has experienced several episodes of very high inflation levels in the past and periodically allowed the use of multiple foreign currencies in addition to the Zimbabwe Dollar (ZWL). At the time of writing of this article in July 2022, consumer price inflation stood at 257% per annum according to Trading Economies (2022) and at 260.63% according to ZIMStat (2022). A strong impact of the hyperinflationary environment has been erosion of depositors' funds and erosion of consumer confidence when new currency measures such as conversion rates have been introduced. This is coupled with other related challenges such as high-interest rates for borrowing and low-interest rates for savings which mainly affect marginalised groups such as women and youths because they cannot access capital thereby further excluding them from the financial ecosystem. Weak consumer confidence is further reflected in the reluctance by MSMEs and general citizens to keep their hard-earned money in banks, opting to keep it in hard currency cash format. This can be attributed to high inflation and a lack of trust in formal financial institutions' capacity to retain the value of their savings. Non-participation in the formal financial institutions further excludes MSMEs and citizens from accessing the broad financial ecosystem.

The Political Stakeholder Dilemma

Through our manifesto analysis tool, we analysed the promises made by two of the most prominent political parties in the Zimbabwe 2018 Presidential election, the Zimbabwe African Union-Patriotic Front (ZANU-PF) and the Movement for Democratic Change Alliance (MDC- Alliance). We noted some references to promoting FI. Both parties referred to promoting entrepreneurship activities through promoting incubation hubs, creating tax breaks and providing access to credit. Neither party mentioned laws and regulations around inclusion and the strategies to improve FI from a policy perspective. Neither party mentioned the importance of training in financial literacy nor enhancing access to information for vulnerable groups. This lack of commitment by political stakeholders is further demonstrated in the analysis of the current GoZ's commitment to promises related to financial inclusion. According to SIVIO Institute's Zimcitizenswatch tracker, two key categories of financial inclusion-related promises that have not commenced as of August 2022 are in the following areas:

- Creating incentives for the introduction of innovative financial products which are easily accessible to the general public.

- Intensifying the rollout of financial literacy programs in collaboration with financial and private sectors.

The absence of solid commitments to FI in the main political parties' manifestos (MDC Alliance, 2018; ZANU- PF, 2018) and the subsequent failure by the government of the day to keep or commence related promises from their election manifestos (SIVIO Institute, 2022) indicates political actors' lack of goodwill in supporting financial inclusion. By extension, it also raises serious doubts about these actors' commitments to integrating citizens' voices and needs in addressing the broad poverty and livelihoods challenges currently facing the majority of Zimbabweans, given the role of these citizens in driving entrepreneurship, growth and success of MSMEs.

Towards A New Thinking for Financial Inclusion in Zimbabwe

Our study shows the same barriers to FI reported ten years ago, raising a fundamental question on the need for a re-think and re-imagination of the mindset and approach used to address FI in Zimbabwe. Other studies supporting these findings include those by non-state actors such as Acacia Economies and FinScope. This demonstrates a misalignment between the design and implementation of policies and intervention mechanisms with the realities of impact for the targeted beneficiaries. This reinforces the need for an approach that is designed to set out a more inclusive and impact-driven framework or thinking for FI. Such a framework or thinking places the citizen and, by extension, entrepreneurs at the centre of policy and intervention design and implementation.

The barriers are well–established and perceptions of what could be done differently can be drawn from the insights from the targeted beneficiaries, thereby creating an opportunity for a more consultative and co-creative approach to designing interventions whose impact can be tracked. In some ways, this should mitigate the re-occurrence of the same barriers in 2030, as is evident from the current discourse. Revisiting the framework for measuring the impact of interventions placing citizen stakeholders such as women and youths at the centre of the framework of new thinking for intervention is a crucial pre-requisite for any initiative that builds on the work done to date to enhance financial inclusion in Zimbabwe.

This is imperative considering the nuances and complexities that frame the Zimbabwean context outlined above. There is need for a deliberate process of engagement of citizens in co-designing and co-creating intervention and impact measurement strategies that are responsive to the lived circumstances of the citizens and, by extension, MSMEs. Citizens and, by extension, MSMEs' decision-making on financial issues is made within a much-nuanced environment that is relatively unique to Zimbabwe.

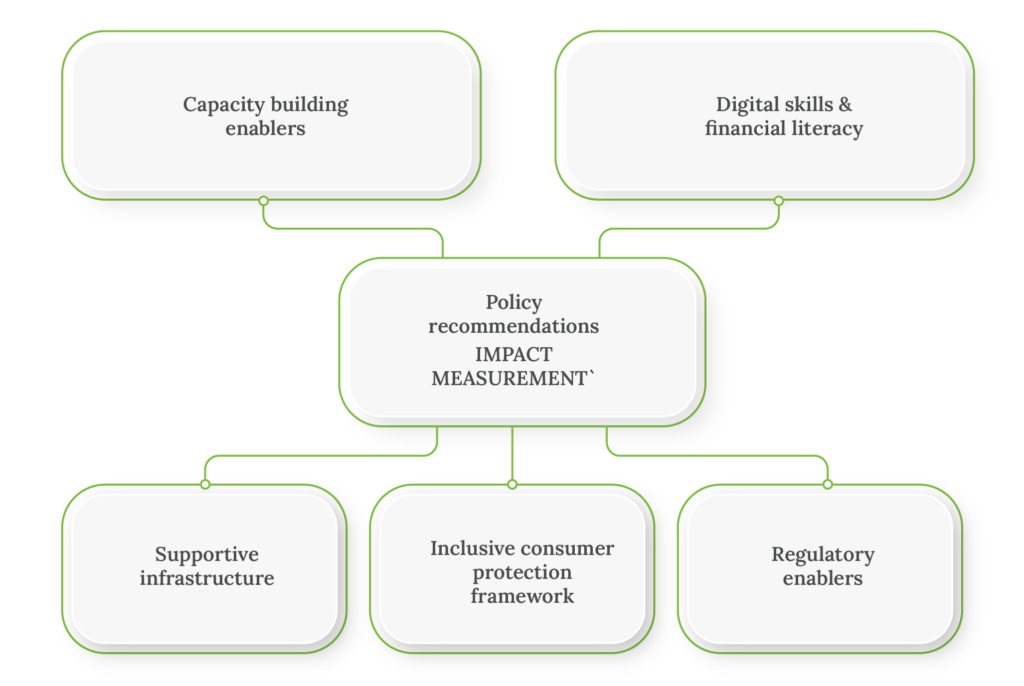

Policy Recommendations To Enhance The Impact Of MSME-Support Initiatives And Financial Inclusion Of Citizens In Zimbabwe

Many programmes have been implemented to promote MSMEs, specifically women-owned and-run MSMEs. There are various sources and case studies that can be used for benchmarking effective policy interventions commissioned by the World Bank and international development actors such as German Technical Cooperation (GTZ), which have been implemented in countries such as Tanzania, notwithstanding the often faulty and contentious one size fits all policy prescriptions of multi-lateral organisations void of local context sensitivities. Figure 3 below summarises a framework to revisit the framing of interventions with an emphasis on continuous co-creative measurement of the impact on citizens' livelihoods.

Capacity Building Enablers-Research and Funding

Given the diversity and continuous barriers to FI in Zimbabwe, there is a need for investment in constant research to measure the impact of interventions that are in place. This process should be co-creative, involving targeted beneficiaries such as MSMEs and women and the generality of citizens currently excluded from the formal financial services ecosystem. Investment in new product development responsive to the nuances and complexities of Zimbabwe's context is essential. This must be reinforced by integrating citizens' voices in co-designing and co-creating relevant financial products. Other key areas of capacity building include the development of a robust Fintech network which will be crucial in improving funding models for MSMEs and, by extension, mentoring marginalised groups such as women. A targeted focus for funding different stages of MSMEs would help entrepreneurs develop and scale up, considering how most enterprises are active in the informal economy. Integration of diverse funding options such as philanthropy foundations and impact investors should be promoted through appropriate policies and incentives for the actors to participate in inclusive financial services ecosystems.

Regulatory Enablers

There is scope to revisit the regulatory environment governing key actors, such as micro-finance institutions (MFIs), in order to reduce the stringent regulations on MFIs. The trickle-down impact of this will be a reduction on the cost of lending money to the poor. This can include reviewing renewal periods for licenses from the costly 12 month period to 24 months. Funding for MFIs in Zimbabwe must utilise mechanisms that target communities at the bottom of the pyramid, in rural and remote areas, by creating a national development fund for MFIs. This will help to ensure that the MFIs get access to affordable and patient capital, which allows them to lend at lower rates with more extended payback periods to vulnerable groups who need the access most.

Restrictive compliance requirements have been cited as key barriers to FI. Therefore, there is a need for a consultative engagement of targeted beneficiaries to understand the constraints they face which inhibit them from complying with registration requirements. Involving all the stakeholders in developing a regulatory framework could enhance the levels of compliance. Other best practices implemented in developing and transition economies include introducing support mechanisms such as tax breaks and loan access which can encourage MSMEs to move into the formal economy.

Pro-poor Reforms

Further pro-poor reform ensures that the 2% IMTT does not apply to low-value transactions and that micro and small enterprises are shielded from the tax. This could be an additional method of promoting compliance through policy support in understanding the impact of MSME on the economy, employment and GDP. These reforms should also be extended to financial product development, where there is a gap in providing insurance and reinsurance products for MSMEs and the poor.

Supportive Infrastructure

In terms of competition, Zimbabwe needs to relax current restrictions in the communications sector to allow for the entrance of new telecom companies that can compete with the few big players. This will help to reduce voice and data costs to consumers, thereby aiding access to technology and, therefore, inclusion. The ability to send money to or receive it from another person even if they use a different financial service provider are critical pre-requisites for broadening access to digital financial products. The current digital telecommunications environment is dominated by one major network, Econet. Pro-market advocates would argue that the government has no business in managing market dynamics in a free market model. However, interventionist policies are a necessity where there is a need to safeguard the provision of public social products such as accessible and affordable telecommunications.

Energy inclusion and financial inclusion are mutually entwined. It is important to note that access to electricity more broadly unlocks access to other essential services, including information and communications technology (ICT), education and healthcare services. Without electricity, it is difficult to expand these services to rural areas. FI can facilitate energy inclusion by allowing access to finance to invest in basic energy needs (such as a solar power system) and by making it possible to pay for electricity using digital payment systems.

Digital Skills and Financial Literacy Training

There is need to promote digital skills that will lead to the promotion of financial technology skills in Zimbabwe, with an emphasis on developing such skills at secondary and tertiary levels. Stakeholders should continue to invest in promoting digital capabilities skills, especially among marginalised groups such as women and youths. This could be best maximised by integrating the various training initiatives implemented by multiple players in the financial ecosystem. An extension of education should include financial literacy training in tertiary education systems so that citizens are introduced to school-level financial literacy training.

Inclusive Consumer Protective Framework

The GoZ and other stakeholders such as the RBZ, have made significant inroads in introducing various policy and legal instruments to safeguard consumer protection in line with the NFIS (See Annex 1). However, there is scope for revisiting these instruments to integrate the voice of targeted beneficiaries, the citizens. The current challenge is not so much about what has been put in place to date, but it is more to do with an evaluation of the implementation and effectiveness of the various instruments that are in place. A citizen-centred approach helps draw insights into some of the nuanced complexities that citizens and, by extension, MSMEs face in utilising the current instruments.

Conclusion and Future Research Directions

Although progress has been made with regards to financial inclusion, it is evident that there has been little change in the challenges that Zimbabwe faces since the FinScope survey of 2012. Thus, although progress is evident it has not been sufficient to remove the hurdles to inclusion. Additional research needs to be conducted to determine the actual impact of current efforts to enhance women's financial inclusion, explicitly considering the recorded successes based on NFIS indicators. Continuous real-time evaluation of the uptake and effects of legislated consumer protection instruments is also critical to future research. The information gathered should address the gaps of information currently existing around the informal sector together with the needs and preferences of vulnerable groups.

We currently note that access has improved since the NFIS but high-quality products and services are not accessed equitably. Therefore, future efforts on inclusion should be aimed at measuring the quality of financial products and services with benchmarks for financial service providers with an emphasis on improving the quality provided to low-income groups. Our quest for information and quality should aim to meet the needs of consumers, understanding that rural and urban communities, men and women, the elderly and the young have different financial needs.

The policies we promote should consider the information and quality gaps with an emphasis on consumer protection and innovation in the digital age. Some industry sectors such as vending, retail, mining and agriculture require diligent efforts to ensure that citizens in those spaces have an opportunity to engage with policy makers on products, services and inclusion measures that would be best suited for them.

Our attention and focus should rightly continue towards women, youth and MSMEs with efforts to reduce their vulnerabilities and promote their inclusion through improved access, improved training and opportunities for co-creation with policy makers.

We observe that the barriers to inclusion for small enterprises can be summed up as lack of flexible and affordable financing, harsh compliance laws and lack of information on the best fit for using and sourcing financial products and services. Addressing these three concerns for targeted groups such as youth, women and founders in marginalised areas will create more inclusive systems that promote access amongst MSME’s.

References

Acacia Economics. (2020). Zimbabwe financial inclusion refresh: Making access possible report. Johannesburg, South Africa: Acacia Economics.

African Development Bank. (2011). From stagnation to recovery - Africa: Zimbabwe report. In ADB (Ed.), Infrastructure and Economic Growth in Zimbabwe (pp. 2-16). Tunisia: ADB.

Ahmed, M.S., & Wei, J. (2014). Financial inclusion and challenges in Tanzania. Research Journal of Finance and Accounting, 5(21) 1-8.

Atkinson, A., & Messy, F. (2013). Promoting financial inclusion through financial education: OECD/INFE Evidence, Policies and Practice. OECD Working Papers on Finance, Insurance and Private Pensions, 34.

Bara, A. (2011). Pursuing inclusive financial development for economic growth: options and strategies. ZEPARU Working Paper Series (ZWPS 06/11).

Barugahara, F. (2021). Financial inclusion in Zimbabwe: Determinants, challenges, and opportunities, International Journal of Financial Research, 12(3) 261-270.

BDEX. (2022). Salaries in Zimbabwe. Retrieved from https://bdeex.com/zimbabwe/.

Brown, A., Mackie, P., Smith, A., & Msoka, C. (2015). Financial inclusion and microfinance in Tanzania. Inclusive Growth (Tanzania Country Report). Cardiff, UK: Cardiff School of Geography and Planning.

Chaora, R. B. (2022). Financial inclusion of micro, small and medium enterprises in Zimbabwe. Harare: SIVIO Institute.

Demirgüç-Kunt, A., & Klapper, L. (2012). Financial inclusion in Africa. An overview. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 6088, June.

FinMark Trust. (2014). FinScope Zimbabwe consumer survey 2014. Retrieved from http://www.finmark.org.za/finscope-zimbabwe-consumer-survey-2014/3.

Gutiérrez-Nieto, B., Serrano-Cinca, C., Cuellar-Fernández, B., & Fuertes-Callén, Y. (2017). The poverty penalty and microcredit. Social Indicators Research 133, 455–475.

International Labour Organisation. (2021). Outside the box - The resilience that keeps the economy moving. Retrieved from https://www.ilo.org/africa/countries-covered/zimbabwe/WCMS_827210/lang--en/index.htm.

Isukul, A.C., & Dagogo, D.W. (2018). Resolving the problem of financial inclusion through the usage of mobile phone technology. Journal of Banking and Finance, 1(1), 1-17.

Isukul, A., & Tantua, B. (2021). Financial inclusion in developing countries: Applying financial technology as a panacea, South Asian Journal of Social Studies and Economics, 9(2), 42-60.

Isukul, A. C., Agbugba, K. I., & Chizea, J. J. (2019). Financial inclusion in a developing country: An assessment of the Nigerian journey. DBN Journal of Economics and Sustainable Growth, 2(2), 94-120.

Kanyenze, G., Kondo, T., Chitambara, P., & Martens, J. (2011). Beyond the enclave: Towards a pro-poor and inclusive development strategy for Zimbabwe. Harare, Zimbabwe: Weaver Press.

Krumer-Nevo, M., Gorodzeisky, A., & Saar-Heiman, Y. (2017). Debt, poverty, and financial exclusion. Journal of Social Work, 17(5), 511-530.

Kumar, R.T. (2017). A comprehensive literature review on financial inclusion. Asian Journal of Research in Banking and Finance, 7(8), 119-133.

Mahmood, S., Shuhui, W., Aslam, S., & Ahmed, T. (2022). The financial inclusion development and its impacts on disposable income. SAGE Open, 12(2). DOI:/10.1177/21582440221093369.

MDC Alliance. (2018). New Zimbabwe pledge for a sustainable and modernization agenda for real transformation. Retrieved from https://rb.gy/afyb8f.

Ngonyani, D. (2022). Financial inclusion in developing countries. A review of the literature on the costs and implications. Financial Studies, 26(1), 54-77.

Orbitax. (2022). Zimbabwe highlights measures of the Finance Act for 2022. Retrieved from https://rb.gy/ykxuii.

Oshora, B., Desalegn, G., Gorgenyi-Hegyes, E., Fekete-Farkas, M., & Zeman, Z. (2021). Determinants of financial inclusion in small and medium enterprises: Evidence from Ethiopia. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 14(7), 286-305.

Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe. (2016). Zimbabwe National Financial Inclusion Strategy 2016–2020. Retrieved from https://rb.gy/ptj5m9.

Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe. (2020). Zimbabwe National Financial Inclusion Journey (2016 to 2020). Retrieved from https://rb.gy/1l7ux1.

Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe. (2022). Mid-Term Monetary Policy Statement. Retrieved from https://rb.gy/hzo9zy.

SIVIO Institute. (2022). Financial Inclusion Index. Retrieved from https://sivioinstitute.org/interactive/financial-inclusion-study.

SIVIO Institute. (2022). Zimcitizenswatch. Retrieved from https://www.zimcitizenswatch.org.

Triki, T., & Faye, I. (Eds.) (2013). Financial inclusion in Africa. African Development Bank (AfDB). Abidjan, Cote d’Ivoire: African Development Bank Group.

Daneshvar, C., Garry, S., Lopez, J., Santamaria, J. & Villarreal, F.G. (2017). Financial inclusion of small rural producers: Trends and challenges. In F.G. Villarreal (Ed), Financial inclusion of small rural producers (pp. 15-26). Mexico: Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean.

Were, M., Odongo, M., & Israel, C. (2021). Gender disparities in financial inclusion in Tanzania. WIDER Working Paper 2021/97. Helsinki, Finland: UNU-WIDER.

World Bank. (2022). Financial inclusion: Financial inclusion is a key enabler to reducing poverty and boosting prosperity. Retrieved from https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/financialinclusion/overview#2.

World Bank. (2021). The Global Findex Database 2021. Retrieved from https://www.worldbank.org/en/publication/globalfindex/Data.

United Nations Conference on Trade and Development. (2021). Financial inclusion for development: Better access to financial services for women, the poor, and migrant workers. UNCTAD/DITC/TNCD/2020/6, 10 February.

Yoshino, N., & Morgan, P. (2016). Overview of financial inclusion, regulation, and education. ADBI Working Paper Series, 591, September.

ZANU-PF. (2018). The people’s manifesto - 2018. Retrieved from https://rb.gy/dggd07.

ZIMSTAT. (2022). Consumer Price Index. Retrieved from https://zimbabwe.opendataforafrica.org/nparigg/consumer-price-index-february-2019-100.

Annex 1: Regulations Governing Financial Inclusion in Zimbabwe

- Money Lending and Rates of Interest Act

- Banking Act

- National Microfinance Policy (2008)

- Microfinance Amendment Act

- Bank Use Protection and Suppression of Money Laundering Act

- Immovable Property (Prevention of Discrimination) Act

- Cooperatives societies act

- Insurance Act

- Exchange Control Act

- National Gender Policy

- Mobile Money Interoperability Regulations of 2020

- Consumer Protection Framework

- Retail Payment Systems and Instruments

- Operational Guidelines for Deposit Taking Micro-Finance Institutions

- Prudential Standards on Agency Banking

- National Financial Inclusion Strategy

- National Development Strategy 1 (NDS 1)

- Zimbabwe National Industrial Development Policy 2019 to 2023

- Infrastructure Investment Plan

- Vision 2030