Introduction

The epistemic decline of the humanities is a reflection of the general decline of humanity (Ikpe, 2015). The ongoing global pushback against humanities subjects has been justified by the argument that humanities have failed to evolve enough to offer contemporary solutions to contemporary problems. However, within the African democracy project, the utility of humanities is supported by history which highlights that the resilience and vibrancy of Africa’s culture is sufficient to effectively respond to current political challenges (Omonzejie, 2017). This is particularly illustrated by the collective (social organization) principle of Ubuntu which is hinged on the collective strength of the society to remedy challenges, to celebrate, to support and to exist (Mbiti, 1969). It is these humanistic practices and principles inherent in Ubuntu which are commonly termed culture in Africa.

It is Amilcar Cabral who stresses the importance of culture when he says:

…to dominate a nation by force of arms is, above all, to take up arms to destroy or at least, to neutralise and paralyse its culture. For as long as a section of the populace is able to have a cultural life, foreign domination cannot be sure of its perpetuation. (Cabral, 1974).

Cabral’s sentiments solidify the fact that culture is the foundation of society and any attempts to destroy the fabric of society requires a systematic dismantle of its culture. The interplay between culture and democratic practices today stands as a cornerstone of societal development and political progress or regress. It is an intimate relationship which binds social development and politics and has far-reaching implications in the formation of norms, the exercise of civic participation, and the functioning of democratic principles.

While this may be so, in many African states, political accountability and transparency are increasingly being placed under scrutiny and the utility of elections is incessantly being questioned. Makahamadze (2019) states that the challenge to electoral outcomes is generally caused by a common belief that the electoral vote has been mishandled and this makes the polls a “lightning rod for social discord.”Adejumobi (2000) adds that electoral processes and outcomes have found themselves as victims in the “…gradual, but dangerous re-institutionalisation of autocratic and authoritarian regimes clad in democratic garb” (p.59). Cognisant of these challenges, I proffer the argument that the democracy project should harness the power of humanities concepts and practices because they offer innovative human-centred solutions that go beyond questions of moral dilemma which they have been resigned to settle.

This study thus, provides a unique moment of reflection within the humanities discipline by exploring the different humanistic tools which have the capacity to provide timely solutions for the present and the future of democracy in Africa. The study endeavours to achieve this by looking at the particular ways in which culture, an integral humanistic pillar, influences democratic norms and practices and the ways in which this important relationship may be leveraged to devise democratic solutions for governance in Africa. However, culture is a broad subject and for the purposes of achieving this study’s objectives, it is important to unpack the definitional issues within the broad spectrum of what is known as culture.

Defining culture

Culture has proven to be a vast and intricate field rich in subtleties which warrants in-depth exploration. Cognisant of this, it is not the objective of this study to deeply delve into the definitional issues related to the subject of culture. However, it is also crucial to provide a working definition as I am well aware that within the humanities, meanings are both encoded and decoded. The term culture generally incorporates a wide range of concepts, including lifestyle, values, etiquette, preferences, and practices (Mirfenderesky, 2002). The cultural theorist Raymond Williams (1976), suggests that culture, broadly or precisely “indicates a particular way of life, whether of a people, a period or a group” (p.6). Similarly, culture is also taken to involve the literature, music, film theatre, paintings, or sculpture of a people (Williams, 1976). Culture can therefore, be defined as the foundation of any given society and within this foundation, religion is central as it is regarded as that which orients society to find its identity (Beyers, 2017). As a result of the existence of culture, society is designed in a manner which is distinct and adaptable to the particular requirements of its environment, thereby, shaping the behaviours and customs of the people. Culture can also be viewed as a framework of how the society engages with itself, that is, endogenously, and with the outside exogenous environment. If one is to also consider the historical definition of “culture” as that which is rooted in agrarian practices, culture is also that which produces within a specific environment (Jahoda, 2012). In light of these definitions, it is reasonable to argue that the formation or establishment of a culture can be traced to a given set of circumstances within the environment. The word “circumstance” here is better placed than “challenge” because the formation of a culture is not entirely founded in reaction to adversity but, can similarly be developed to harness positive outcomes in society. These practices, customs, actions, values, and preferences shape norms which influence not only social development, but also politics and democracy at large.

Methodology

This study was conducted through ethnographic research in The Gambia during the months of October to December 2021 on the prelude to the presidential elections. As defined by Brewer and Sparkes (2011) ethnography is the study of people in their natural contexts. The central aim of ethnography is to generate profuse accounts of peoples’ lives and is especially effective in making sense of the messy particularity of lives in different contexts and cultures. It is the central aim of ethnography to make the strange, familiar. Accordingly, an ethnographic approach was important to my empirical enquiry into the ways in which cultural norms and practices of The Gambia influence democracy. Ethnography gave me access to the Gambian people’s socio-cultural lives, their often hidden social-cultural reality and the meanings they attach to these. The research was specifically conducted in the Upper River Region (URR), employing the staple ethnographic tool of participant observation. During the research period, I assumed the role of a long-term election observer and this role provided me with valuable information to develop profound understanding of governance in The Gambia and to gain an appreciation of the socio-cultural diversity characterising this nation. As Moriarty (2011) explains, participant observation in ethnography allows the researcher to acquire insights beyond what can be obtained through interviews alone, thereby potentially opening new avenues of inquiry and understanding. Participant observation, therefore, opened up new avenues of socio-cultural inquiry and comprehension of the nexus between cultural practices and democracy in The Gambia.

The nexus between culture and democratic practices

The nexus between culture and democracy in Africa cannot be fully understood outside the history of colonialism which imposed Eurocentric cultures and practices in Africa and sought to establish them as the norm. Cabral (1974) explains this when saying:

…experience of colonial domination shows that, in the attempt to perpetuate exploitation, the coloniser not only creates a whole system of repression of the cultural life of the people colonised, but also arouses and develops the cultural alienation of a section of the populace by the so-called assimilation. (p.14).

Mimoko (2010) expands on this issue by arguing that traditional African systems of conflict resolution were destroyed by colonialism, and, in their place, nothing was given. Mimoko further argues that the democratic processes in Africa were brutally uprooted by a deliberate erasure of African indigenous cultures. This shows how culture and democracy in Africa and perhaps beyond Africa, have an intimate correlation. Cultural norms influence the development of political habits and these habits, in turn, inform democratic practices. Elections, constitutionalism, pluralism, and tolerance are some of the democratic practices that are rooted within strong cultural foundations. The prevailing attitudes and behaviours of the society can provide a disabling or enabling environment for the exercise of democratic customs, thereby, accentuating the importance of culture in the attainment of democracy (Inglehart & Welzel, 2003). The practice of democracy formalises civic and political participation based on an established framework (Inglehart & Welzel, 2003). For this formal structure to function, it is highly dependent on the informal organisation within a particular community and the foundation for such informal organisation is culture. If the culture within the environment is cultivated to be intolerant of divergent views, the application of formal democratic practices becomes difficult. The nexus between cultural norms and democracy lies in the fact that for democracy to flourish, the cultural foundations of society must create a conducive environment for that to happen. The flipside to this perspective is that democracy has the potential to shape the culture of a society. This implies that democracy might impose its values on culture instead of culture naturally engendering democracy. Scholars such as Hu (2013) stress the importance of harnessing the influence of culture in the realm of politics, suggesting that this approach is more effective than resorting to the tools of warfare.

Up to this point, culture has been defined as a distinctive way of life within a specific group and time frame. Additionally, it has been shown that culture is linked to the origination of religion, norms and values through socialisation thus, highlighting an inherent contrast between norms and values on one hand and attitudes and beliefs on the other. While both are encompassed within the framework of culture, the notable resilience of norms and values against external influences compared to attitudes and beliefs strengthens the argument that culture plays an important role in shaping democratic norms. It is, important to emphasise that culture is not static, it is fluid and dynamic and reflects the proclivities of the times. However, despite this fluidity, traditional norms and values remain the substratum of society undergirding democratic principles and practices. The Gambia presents a perfect example of the intimate correlation between culture and democracy, particularly the ways in which the Gambian culture has been used during elections to influence democratic practices. In order to fully appreciate how socio-cultural norms have been utilised to advance democratic practices in The Gambia, it is necessary to provide a brief historical background of the country.

The Gambia: A brief background

The Gambia is a West African State which was the last British colony in West Africa to gain its independence in 1965 (Edie, 2000). It is characterised by a fusion of cultures emanating from various ethnic groups including the Mandinka, Fulani/Tikular, Wolof, Jola/Karoninka and Serahuleh among many others. Additionally, the country’s religious set up is comprised of 90% Islam, 8% Christianity, and 2% indigenous traditional religion (Sanneh, 2017). Like numerous African nations, The Gambia has experienced a tumultuous past marked by periods of both peace and conflict, where the state has sometimes resorted to force and other times adhered to constitutional principles to assert its authority. The nation's political trajectory has been extensively chronicled, with a significant milestone being the unveiling of the Truth Reconciliation and Reparations Commission (TRRC) report in 2021. This comprehensive report meticulously recounts historical events within the country, spanning from the 1994 coup, the 1999 witch hunts, sexual and gender-based violence offences, the president's Alternative Treatment Programme and various other historical atrocities. While the TRRC report’s intentions were noble, there is a glaring absence of the role played by cultural norms and practices within the grand scheme of all these atrocities. Yet, it is important to acknowledge that culture has played and continues to play a substantial role in Gambian politics, past and present. It is therefore this study’s objective to place Gambian cultural norms and practices in conversation with political practices in order to show the specific ways in which cultural norms and values influence election campaigns and voting processes. For this objective to be achievable, it is correspondingly important to provide a general overview of the drivers of culture in The Gambia.

Drivers of culture in The Gambia

The drivers of culture in The Gambia are varied and nuanced but the most common drivers of Gambian culture are religion and tradition. In The Gambia, cultural practices and customs largely follow the Islam religion. It was the former President Jammeh of The Gambia who boldly declared that The Gambia would become a truly Islamic country, and that the country’s constitution shall be the Quran. Following up on this declaration, Jammeh pronounced that female government employees had to wear headscarves in accordance with the dictates of Islam religious practices. While this new law was quickly shut down, Jammeh’s pronouncements illustrated the ways in which religion entangles with political processes in The Gambia. Scholars such as Sanneh (2017) share the view that Jammeh’s actions reflected the genesis of a wider political campaign tactic which was targeted at thwarting political opposition in the country. While Jammeh’s motivations for imposing Islam religious norms and practices in The Gambian state craft may be contested, what is clear is that religion cannot be separated from The Gambian political practices and governance issues. This is made clear in the TRRC report where it says:

The Gambia is a multi-cultural and religious society where religious leaders are held in high esteem and have the power to sway public opinion. They are often perceived as the intermediaries who interpret God’s word and laws. Culturally, the belief in spirits and spiritual knowledge, and supernatural beings comes from a belief that some people (mostly religiously trained people) possess supernatural knowledge about these things.[1]

The religion and politics node in The Gambia is made even more apparent by the fact that political practices such as Local Government Elections do not coincide with Ramadan, a sacred month in the Islamic calendar (Jaiteh, 2022). Ramadan is observed by Muslims across the globe as a period of prayer, fasting, deep reflection and community. In The Gambia, Ramadan should not coincide with elections based on the argument that the electorate's attention is drawn to prayer and fasting and this hinders their ability to fully participate in politics. This underscores the substantial role of religion in shaping the socio-political fabric of The Gambian society.

Tradition also plays an important role in shaping the political culture in The Gambia. For example, the Alkalo[2] and the chiefs are the traditional leaders who have the political and governance reigns at the village level (Hughes & Perfect, 2008). The Alkalo holds significant authority to the extent that they have in the past, been regarded as part of the political architecture of the People’s Progressive Party of Dawda Jawara. Their immersion with the local communities and their religious hold on the people was used strategically to push the party’s political agenda (Edie, 2000). Within the framework of post-colonial governance, the Alkalo have been accorded defined administrative duties but they would also use these duties to register and coerce the electorate towards the ruling party using incentives from the central government (Edie, 2000). This demonstrates how the Alkalo traditional leadership has been strategically placed to influence the vote outcome at the expense of opposition political parties.

Communal living remains a prevalent traditional practice in The Gambia and the role of the Alkalo has evolved to encompass conflict mediation, preservation of tradition, and the facilitation of voter mobilisation within the communities. Furthermore, within the traditional context, gatherings take place at the Bantaba, typically beneath a Bentennie tree where discussions driven exclusively by men take place. These discussions range from social challenges faced by the communities to issues of community development. Typically, traditional culture in The Gambia profoundly shapes societal norms, delineating specific roles and restrictions for men and women and these restrictions in turn spill over into the political arena. My exploration of the influence of culture on democratic norms and practices in The Gambia, confirmed the central role played by religion and tradition in driving cultural practices in this country. It also revealed the existence of many other unique cultural practices and these were made more apparent during political campaigns.

Unique cultural practices and political campaigns in The Gambia

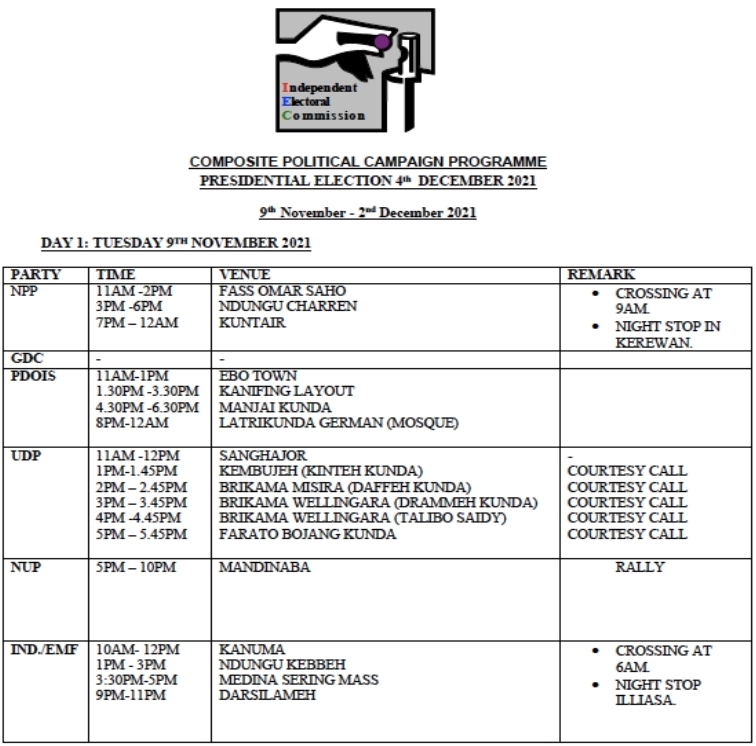

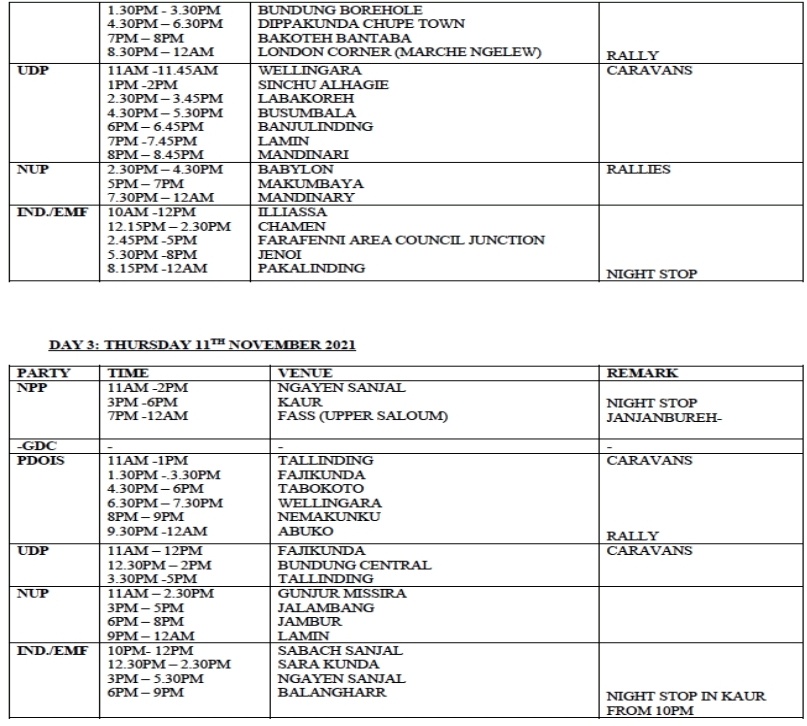

In The Gambia during elections, as in many election environments, political campaigns become vibrant spectacles of music and political grandeur as candidates compete to outshine one another in their quest for political victory. The political campaigns are set with custom trucks, mobile screens, live music bands, dazzling lights, and motorcades, which are all strategically employed to convey political force and dominance (Paget, 2023). In many African countries, electoral campaigns are typically held during the day so as to maximise on the number of people who can attend these political “shows.” However, in The Gambia, campaigns distinctly take place during the day and night as illustrated in Figures 1 & 2 below:

Figure 1: Campaign programme, 9th November 2021

Figure 2: Campaign programme, 11th November 2021

Political campaigns in The Gambia are methodically allotted times which range from 11a.m to 12a.m and these times are uniform across the political party divide. One of the major reasons for such an arrangement is so that political activities during elections do not disrupt the usual business of the day. The time slots are meant to be inclusive and they represent a regular and integrated process within the country’s political milieu. Gambian election campaigns are designed in such a way that they do not bring the country’s daily business to a halt. They are amalgamated into the daily business of the day and night so as to be as inclusive as possible and not leave behind or exclude anyone who may be interested in attending or participating in the campaign performances. This typically reflects The Gambia’s traditional cultural values which are communal in perspective. Traditional governance politics in The Gambia is decided by everyone, it is communal and for these communal political values to succeed, everyone should be involved.

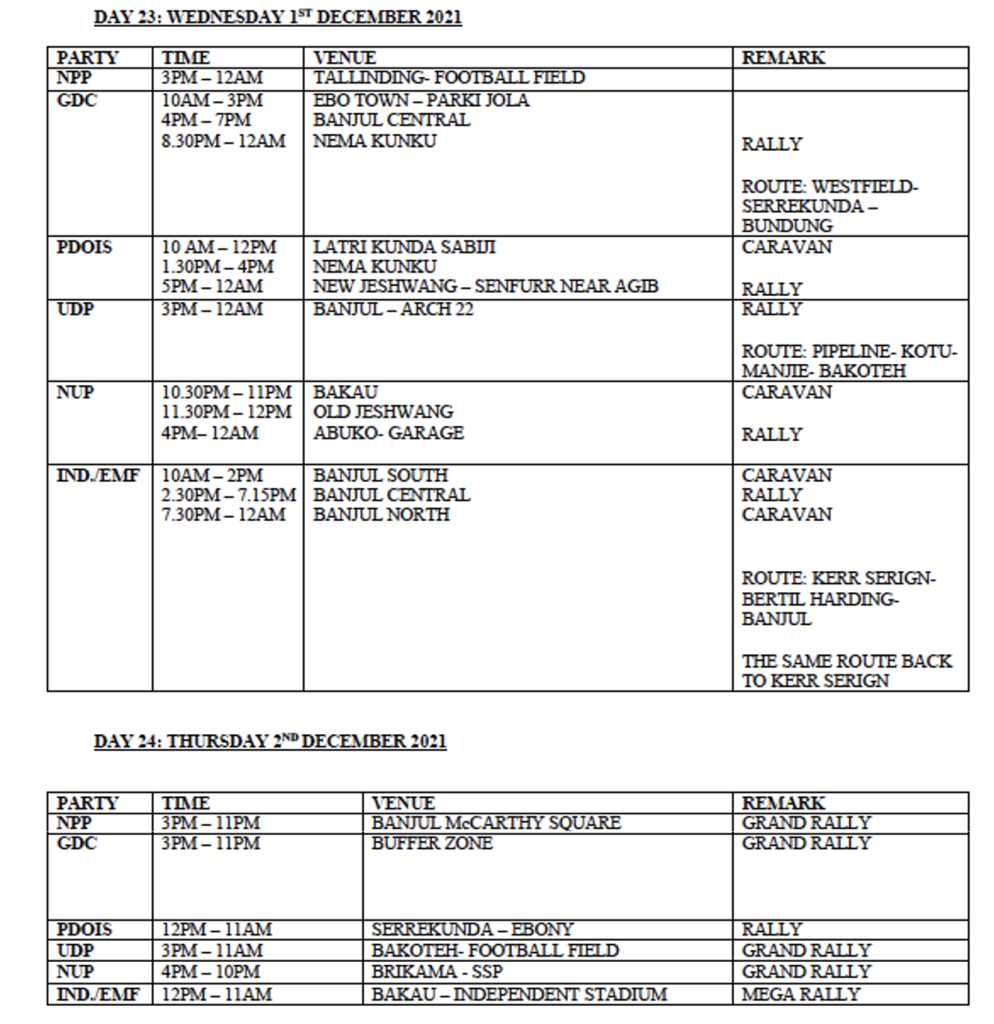

Within this framework of inclusivity, political campaigns in The Gambia practice what is popularly known as “crossing”. “Crossing” is a situation whereby different political parties are expected to cross paths at an intersection or along the highway during a campaign trail. Usually, crossing happens when one political party is headed to the location where another party is leaving.[3] While this kind of political party intersection is not common in many African countries, in The Gambia it is encouraged so as to promote political tolerance and dialogue. Political tolerance is a practice engrained in Gambian traditional culture and emanates from the recognition that while there may exist political differences, these differences do not overshadow the fact that they are one people. Consequently, contemporary election campaigns in The Gambia are characterised by peace and not chaos. The climax of peaceful campaigning was played out in the first ever presidential debate which happened on the 20th of November 2021 when the two presidential candidates were given a public platform to debate their policies and presidential plans for the country. At the centre of presidential debates is the idea of public dialogue which is a common feature of traditional political culture in The Gambia. In addition, the fact that some political rallies can go on until the middle of the night is a testimony to how tolerance and respect for political differences provides safe spaces for doing politics. Safe spaces for political campaigns continue to be cultivated through early cultural socialisation to tolerance and the doctrines of dialogue and respect for everyone are insisted upon. The practice of “crossing” political routes, which is illustrated in Figure 3 below, becomes a practical method of achieving political tolerance and dialogue. Tolerance is thus, not just a buzzword which Gambian politicians throw around, it is a way of life intricately connected to the cultural norms and practices of The Gambia. Beyond the political campaigns, the influence of culture on democratic process is also evident in the voting systems of The Gambia as will be discussed in the following section.

Figure 3: Campaign programme, 1st December and 2nd December 2021

Voting systems

While contemporary elections and voting processes in The Gambia appear to be open and tolerant, it must be said that its past processes were not as smooth sailing. One of the major challenges faced by the country during elections was the problem of vote buying in exchange for basic food commodities such as rice. There is a sense in which The Gambian politicians of days past took advantage of the electorate’s generally impoverished conditions and political illiteracy to lure them into voting for them with food and other basic commodities. According to Foon (1961), vote buying happened in such a way that the voter would receive their ballot papers as is the standard procedure. However, upon getting into the voting booth, the voter would not cast their vote but would instead leave the voting booth with their ballot paper and proceeded to trade these for food and other commodities. The rampant problem of vote buying resulted in the introduction of the marble token and the bell drum ballot which is now common in contemporary Gambian elections. The ballot drum (Figure 4 below), works in such a way that the marble token is deposited in the drum when a vote is cast and whenever the marble falls in the drum, a bell rings signifying that a vote has been cast. The polling officers therefore listen for this sound as a way of making sure that the voter has placed their ballot in the drum and does not sneak out of the polling station with their ballot papers.

Figure 4: Ballot drum pre-deployment sorting

To identify the candidate of the voter’s choice, the ballot drums are coloured according to the candidate’s campaigning colours thereby minimizing the risk of votes being cast for the wrong candidate (see Figure 5 below)

Figure 5: Ballot drum pre deployment assessment

The marble and drum voting procedure may not be at par with international voting systems which have evolved technologically and continue to be re-dynamised, however, it remains an inclusive system of voting which takes into consideration the needs of all the electorate. Before the marble ballot and drum, the terrain of participation in political processes was not even, as it tended to disadvantage those people who were not literate. It also exposed them to manipulation from scheming political candidates. The marble and drum created an even platform where even the most illiterate people are able to understand the voting systems and how to go about casting their vote. The concept of the marble ballot speaks well to the communal nature of governance which is characteristic of The Gambian traditional culture. One can argue that it aligns well with democratic practices in the way it shuts down electoral fraud caused by vote buying. The fact that this new system was not imposed from the top, but, was a result of collective agreement shows how power is not something that comes from the top, but is enabled by people from the grassroots. Democratic electoral practices are often shaped by integrity and it is the integrity of the polls which the new marble ballot endeavours to uphold. The fact that The Gambian people were open to a new electoral system which is good for all cements the idea not just of the fluidity of culture, but of how culture may evolve to meet the new political needs of the society.

Foon (1961) has this to say:

By cutting out the possibility of fiddling before, during or after the election, each person can truly, without fear, favour or intimidation, vote in complete security according to his own conscience. We might then be able to consider policies rather than personalities, for upon those who, by threat or bribes, endeavour illegally to influence for their own ends a person's constitutionally guaranteed right to vote, will rest the full responsibility for any recriminations, bitterness or actual disturbance arising from The Gambia's first general election under full universal adult suffrage. (p.37)

Foon rightly points to the democratic values that were meant to be upheld through the new voting system. This is not to say that the new system is without its weaknesses. One of the major challenges with the marble ballot is that it sometimes fails to cater for the increase in the numbers of the candidates which in turn requires more marbles and drums. Despite these challenges, it goes without saying that The Gambian cultural norms and practices which are rooted in tolerance and inclusivity make way for equally inclusive democratic practices which enhance electoral confidence and integrity allowing for social cohesion during elections.

Conclusion

As the study has revealed, it cannot be overemphasised that humanistic tools such as culture provide valuable guidance, much like a compass, for addressing society's core challenges and for enabling democratic norms and practices not just in The Gambia, but potentially across the African continent. Looking at how the African continent continues to grapple with democratic governance issues, I proffer the argument that African countries should consider all possible ways for achieving democracy. Culture is collective and the collective is always political, thus, culture provides an untapped resource for concepts and methods of doing democracy in Africa. The study rightly showed the significance of culture on democratic principles and values. Through the case study of elections in The Gambia, the study showed that a society's capacity to adjust, to coexist, and to operate hinges on the foundation of cultural norms and values which are fostered within that community. Socialisation through religious and traditional beliefs are shown to play a dominant role in developing the core democratic values in The Gambia. Hence, culture is some sort of internal compass that is developed through socialisation and can be very useful in building tolerance, inclusivity, respect and transparency.

References

Abubakar, S. O., & Olasupo, M. A. (2015). Political Socialization and Social Harmony in China: Policy Lesson for President Buhari Administration of Nigeria. IOSR Journal Of Humanities And Social Science (IOSR-JHSS), 75-81.

Access Gambia. (2009). Bantaba in Gambia. Retrieved from Access Gambia: https://www.accessgambia.com/msite/m-bantaba.html

Adejumobi, S. (2000). Elections in Africa: A Fading Shadow of Democracy? International Political Science Review, 59-73.

Bewaji, J. A. (2017). LIberation Humanities. In J. A. Bewaji, K. W. Harrow, E. E. Omonzejie, & C. E. Ukhum, The Humanities and the Dynamics of African Culture in the 21st Century (pp. 4-32). NewCastle: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

Beyers, J. (2017). Religion and culture: Revisiting a close relative. HTS Teologiese Studies/Theological Studies, 1-9.

Brewer, J., & Sparkes, A. (2011, December 2). The meanings of outdoor physical activity for parentally bereaved young people in the United Kingdom: insights from an ethnographic study. Journal of Adventure Education & Outdoor Learning, 11(2), 127-143.

Cabral, A. (1974). National liberation and Culture . Inidiana University Press.

Edie, C. J. (2000). Democracy in The Gambia: Past, Present and Prospect for the Future. Africa Development / Afrique et Développement, 161-198.

Encyclopædia Britannica. (2023, August). Retrieved from The Gambia: Ethinc composition: https://www.britannica.com/place/The-Gambia#/media/1/224771/223909

Foon, M. (1961). Operation Ping-Pong to beat Votes Fiddlers. Journal of African Administration, 35-37.

Hu, Y. (2013). Institutional Difference and Cultural Difference: A Comparative Study of Canadian and Chinese Cultural Diplomacy. The Journal of American-East Asian Relations, 256-268.

Hughes, A., & Perfect, D. (2008). Historical dictionary of The Gambia. Plymouth: Scarecrow Press, Inc.

Ikpe, I. B. (2015). The Decline of the Humanities and the Decline of Society. Theoria: A Journal of Social and Political Theory, 50-66.

Inglehart, R., & Welzel, C. (2003). Political Culture and Democracy: Analyzing Cross-level Linkages. Comparatice Politics, 61-79.

Jahoda, G. (2012). Critical reflections on some recent definitions of ‘‘culture’’. Culture and Psychology, 289-303.

Jaiteh, B. (2022). The Voice Gambia. Retrieved from President Barrow, Gambian Imams should seek for postponement of LG Elections from IEC: https://shorturl.at/ckpzC

Makahamadze, T. (2019). The Role of Political Parties in Peacebuilding Following Disputed Elections in Africa: The Case of Zimbabwe. Africa Insight, 142-158.

Mbiti, J. S. (1969). African Religions and Philosophy. London: Heinemann.

Mimoko, N. O. (2010). Would Falola frustration suffice?: Tradition, governance, challenges and the prospect of change in Africa. In T. Falola, & N. Afolabi, The man, The mask, The muse (pp. 635-650). North Carolina: Carolina Academic Press.

Mirfenderesky, J. (2002). Culture Is What People Do Not What They Should Do. Fortnight, 22-24.

Moriarty, J. (2011). Qualitative methods overview. London: London School of Economics and political science.

Omonzejie, E. (2017). Introduction. In J. A. Bewaji, K. W. Harrow, E. E. Omonzejie, & C. Ukhum, The Humanities and the dynamics of African Culture in the 21st Century (pp. 1-4). Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

Paget, D. (2023, August ). Elections in Africa are won through rallies – but those rallies are changing. Retrieved from Democracy in Africa: https://democracyinafrica.org/elections-in-africa-are-won-through-rallies-but-those-rallies-are-changing/

Sanneh, B. A. (2017). Culture, Religion, & Democracy in The Gambia: Perspectives from Before and After the 2016 Gambian Presidential Election. Juniata Voices, 124-136.

Williams, R. (1976). Keywords: A vocabulary of culture and socitey. New York: Oxford University Press.

[1] Volume 1 Part A TRRC Report https://www.justiceinfo.net/wp-content/uploads/Volume-1-Compendium-Part-A.pdf

[2] The Alkalo is the traditional Gambian village Chief of the founding family however, today they are elected.

[3] Observed by the author in the Upper River Region in The Gambian election of 2021.